Roger Farmer has taken a new look at an issue concerning the Federal Reserve’s program of large-scale asset purchases (referred to in the popular press as “quantitative easingâ€) that I’ve been discussing on Econbrowser and in my research with University of Chicago Professor Cynthia Wu for some time.

research with University of Chicago Professor Cynthia Wu of how LSAP might affect interest rates is that if the Fed takes a large enough volume of long-term securities out of the hands of private investors, the drop in net supply could in principle lower the yields on those securities. In the years since the collapse of Lehman in September 2008, the Fed’s total assets more than quadrupled, and the Fed’s share of the total Treasury debt that was held in the form of longer-term securities increased significantly.

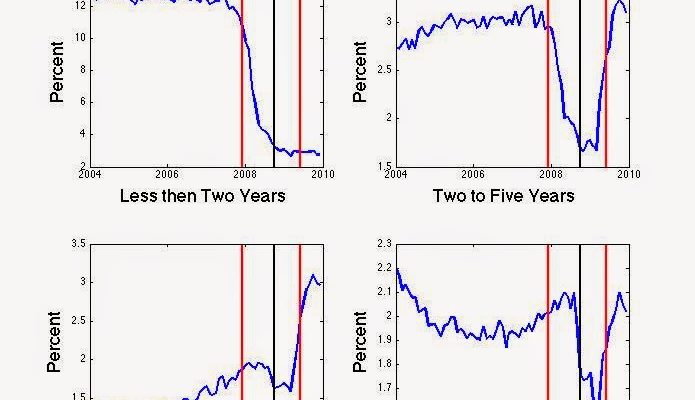

Percent of total Treasury debt held by the Federal Reserve in different maturity categories. Red lines mark beginning and end of the recession, black line marks Sept 2008. Source: Roger Farmer.

But at the same time that the Fed was buying long-term Treasury debt in order to take these securities out of the hands of private investors, the Treasury was significantly increasing the fraction of debt that it issued that came in the form of longer maturities. The net result was that the fraction of Treasury debt that was of 2-10 year duration and that was held outside of the Federal Reserve actually increased significantly, despite the Fed’s bond-buying efforts. Thus according to one theory of how LSAP might affect the economy, all the Fed’s LSAP accomplished was to incompletely offset a contractionary impulse originating from the Treasury’s separate maturity issuance decisions.

Percent of total Treasury debt held by the public in different maturity categories. Red lines mark beginning and end of the recession, black line marks Sept 2008. Source: Roger Farmer.

A number of researchers have documented that on the days that changes in LSAP policy were announced there were noticeable changes in long-term interest rates; see for example Christensen and Rudebusch (2012). This evidence suggests that LSAP did indeed matter for yields. Notwithstanding, at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference two years ago, Columbia Professor Michael Woodford noted that the net move in long-term interest rates over the entire duration of these programs provided little evidence to convince the skeptics. The 10-year yield actually rose between the beginning and end of the Fed’s first bond-buying program (LSAP1). The common interpretation is that some of the declines in the yield prior to the first purchases were actually a response to announcements and anticipation that the program was coming. Even so, any effects during the year of the program were evidently outweighed by other factors influencing bond yields that were changing at the same time. Nor are effects during the actual period when the Fed was engaged in its second bond-buying program (LSAP2) nor its deliberate effort to extend the maturity of its portfolio (MEP) particularly easy to spot in a long-term graph.