Image Source:

Image Source:

To everything turn, turn, turn

There is a season turn, turn, turn

And a time to every purpose under Heaven

A time to be born, a time to die

A time to plant, a time to reap

A time to kill, a time to heal

A time to laugh, a time to weep

To everything turn, turn, turn

There is a season turn, turn, turn

And a time to every purpose under Heaven

A time to build up, a time to break down

A time to dance, a time to mourn

A time to cast away stones

A time to gather stones together

To everything turn, turn, turn

There is a season turn, turn, turn

And a time to every purpose under Heaven

A time of love, a time of hate

A time of war, a time of peace

A time you may embrace

A time to refrain from embracing

To everything turn, turn, turn

There is a season turn, turn, turn

And a time to every purpose under Heaven

A time to gain, a time to lose

A time to rain, a time of sow

A time for love, a time for hate

A time for peace, I swear it’s not too late

– Turn, Turn, Turn, by Pete Seeger

I said last week that, if investors had been anticipating a Trump win and he won “I would expect stocks to sell off and bonds to rally (rates fall)”. I also said that if Harris won, we would get the same result although more severe because Trump supporters who bought stocks anticipating his win would sell. I also said:

Even if you had a crystal ball and knew who was going to win the Presidency and control of Congress, that wouldn’t assure that you know how the markets will react anyway.

Of those predictions, the one I got most right, by far, was the last one, which I proved in very public fashion. Even assuming an outcome, as I did, I got the market reaction wrong. Apparently there are a lot of Trump supporters who have been sitting out the stock market during the Biden interregnum and felt the need to get invested immediately after his win. I was right about the bond market but not initially. At its high the day after the election, the 10-year Treasury yield was up 18 basis points and closed higher by 12. It was over the next two days that bond yields fell and closed the week lower than where they started. As for stocks, they were bid from the open Wednesday to the close on Friday with barely a down hour much less a down day. What is interesting about the market reaction is not that I got it wrong – I claim no ability to trade in such a short-term manner – but rather the contradictory nature of the moves. Stocks – and especially small and mid-cap stocks – rose as if the new Trump term will usher in a boom while bonds acknowledged no such likelihood. Nominal and real long term rates fell while short term rates rose slightly, the combination producing slightly lower real growth expectations and slightly higher inflation expectations. None of the moves were significant enough to draw any firm conclusions but directionally bond investors obviously didn’t buy the boom narrative.One possible explanation is that the move in stocks was not based on an economic boom but rather a profits boom. The obvious problem with that thought is that one generally leads to the other. It is hard for corporate earnings to grow faster than the economy for any significant length of time although they certainly can in the short run. Is there some economic policy anticipated from the new administration that would produce such an outcome? The obvious choice is tariffs where Trump’s campaign trail promise was to raise tariffs on everything, which stock investors could interpret as favorable to all – or almost all – American companies. That reasoning could also help explain the move in bonds. The US – and the rest of the world – has a lot of experience with tariffs throughout history so the effects are pretty well known and almost universally agreed upon among economists of the left and right. Tariffs are nothing more than taxes on imports and the most basic explanation of their effect is that they favor domestic producers over domestic consumers; the effects of tariffs are largely redistributive. It is a lot more complicated than that and I’m sure I’ll be writing a lot about tariffs over the next four years but for now that is the big picture. If you tax consumption, as a tariff does, you will get less of it, but, at least theoretically, you should get more savings and investment. The question is whether the rise in savings and investment can offset the negative on the consumption side. Since consumption is 68% of GDP and private investment is just 18%, the math is difficult to say the least. Lower economic growth is the expected outcome of higher tariffs and so yes, lower bond yields make sense.As for inflation, as with the explanation of tax incidence (who pays) the public discussion has been wanting in many ways. Tariffs would seem inflationary at first glance because the price of imports rises and that allows US companies to increase prices as well. It also means a lower supply of goods and services in the economy and, assuming the money supply doesn’t contract, you have the same amount of dollars chasing a shrinking amount of goods, which sounds like a great recipe for higher prices. But of course, those conclusions assume everything else stays the same which they most certainly will not. Other countries will enact their own tariffs which will reduce US exports and so some goods, once destined for foreign shores, will see an increase in their domestic supply.Retaliation by the countries hurt by our tariffs will be in areas where we are vulnerable. Did you know that China controls 80% of the world’s gallium supply? And that the US hasn’t produced arsenic since the mid 1980s? Did you know that gallium arsenide chips are in everything you use from cell phones to microwaves? Did you know that gallium arsenide chips operate faster with lower power consumption that silicon chips? If I found all that out with a few clicks of the mouse, don’t you think China knows that too? Do you think anyone can pinpoint the exact impact all these change will have on the inflation rate? What’s the price of a product you can’t make?Tariffs have been a part of the American economy since its founding and have been the source of many internal conflicts, not least the Civil War. In 1828, a man who shared my surname*, John C. Calhoun, labeled the tariff legislation of that year as the Tariff Of Abominations and wrote what became known as the South Carolina Exposition and Protest against it. His argument – simplified – was that the Federal government could not enact a tax that benefitted one part of the country at the expense of another and that states had the right to nullify any legislation that did so. South Carolina ultimately did that with the Tariff of 1828, the only state to do so. In the end, a compromise tariff was enacted in 1832 that ended the impasse but that was the beginning of the friction that ultimately led to the Civil War conflagration. Yes, the obvious cause was slavery but tariffs lit the fuse.The ideas that animate today’s modern Republican party, the ideas that led them to a sweep of this election, are ones that dominated the party nearly 200 years ago. The Republicans of the nineteenth century, Abraham Lincoln very much included, would have approved wholeheartedly of the tariff regime proposed by President-elect Trump, who spoke glowingly of Republican William McKinley on the campaign trail as having successfully used tariffs in the late 1800s. In the election of 1896, McKinley was elected, ironically, over the populist William Jennings Bryan who argued against tariffs for raising prices and as being injurious to the working class:

Protection does not make good wages. Our better wages are due to the greater intelligence and skill of our workingmen, to the greater hope which free institutions give them, to improved machinery, to the better conditions that surround them, and to the organizations which have been formed among the wage-earners.

There is a big difference between the America of today and the America of the 19th century. We were then what is known today as a “developing country” and tariffs were used most often as a means of raising revenue and, to a lesser extent, to protect developing industries. In Calhoun’s argument against the 1828 tariff, however, he talked of the difference between a protective (punitive) tariff and a revenue tariff. The former, often applied unevenly and at a high rate, is meant to protect selective native industries from foreign competition and severely restricts imports of specific goods. The latter is generally applied evenly across all imports and at a rate that doesn’t severely restrict imports. He also pointed out that once the tariff rate passed a certain point – became punitive – it would produce less revenue than a lower rate. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it is the same argument revived in the late 1970s by Art Laffer as a justification to cut income taxes. Tariffs will raise more revenue with a higher rate until they reach that maximum yield point, the obvious problem being, just as with income, no one knows where that point is. It is almost certainly different today than it was in 1828 or 1896. Whether President Trump enacts a protective/punitive tariff or a revenue tariff is very important. A protective tariff has many negative side effects and could have a very large impact on the economy. A revenue tariff, even at a significantly higher rate than prevails today, could raise revenue and avoid the worst effects of a protective tariff. Hopefully, Art Laffer will have a talk with him about the difference. Even if it is a revenue tariff, William Jennings Bryan was right about the effect on prices. However, I would not call tariffs inflationary, which implies an ongoing rise in prices. Any price change from tariffs would likely involve a one time change in the price level. I don’t think most people would care about the difference. We don’t know yet exactly what the new Trump administration will do with tariffs or any of his other myriad campaign promises so it is impossible at this juncture to formulate any tactical portfolio response that isn’t purely speculative. We don’t know, for instance, if the tariffs will be as high as he talked about on the campaign trail or if they will be used as a negotiating tool. We don’t know if they will be phased in or raised dramatically in one fell swoop. We don’t know if Republicans will have complete control of Congress, even though that seems to be the consensus thinking right now, and so we don’t know if he will be able to extend his past tax cuts or pass new ones. We don’t know if he will really reduce spending as dramatically as Elon Musk has indicated – but if I were a betting man I’d say no. The song at the top of this commentary is most often credited to The Byrds although many other artists recorded it before they did in 1965. It was actually written by Pete Seeger but he only added six words. The rest of it comes from Ecclesiastes which is generally credited to King Solomon who is often called the wisest man who ever lived. The song, and the King James bible version of it, tells us that change is inevitable, that there is a natural ebb and flow of ideas and perspectives throughout the past and the future. It tells us that ideas and circumstances return over and over, that there is a permanence even in change. There is nothing new under the sun. And so today, the Trump administration is preparing to enact 19th century economic policies and I’m trying to understand how they’ll impact a 21st century economy. As the song says, turn, turn, turn, for everything there is a season.*Whether my family is related to John C. Calhoun is a matter of dispute in my own family. I don’t know and don’t care.

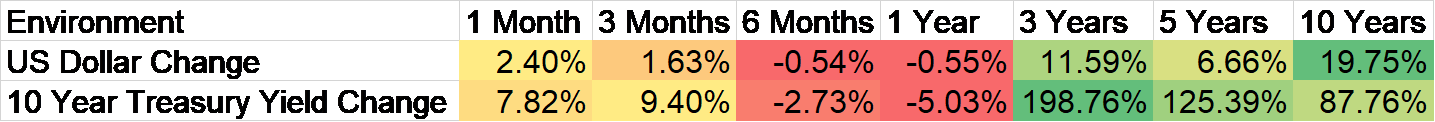

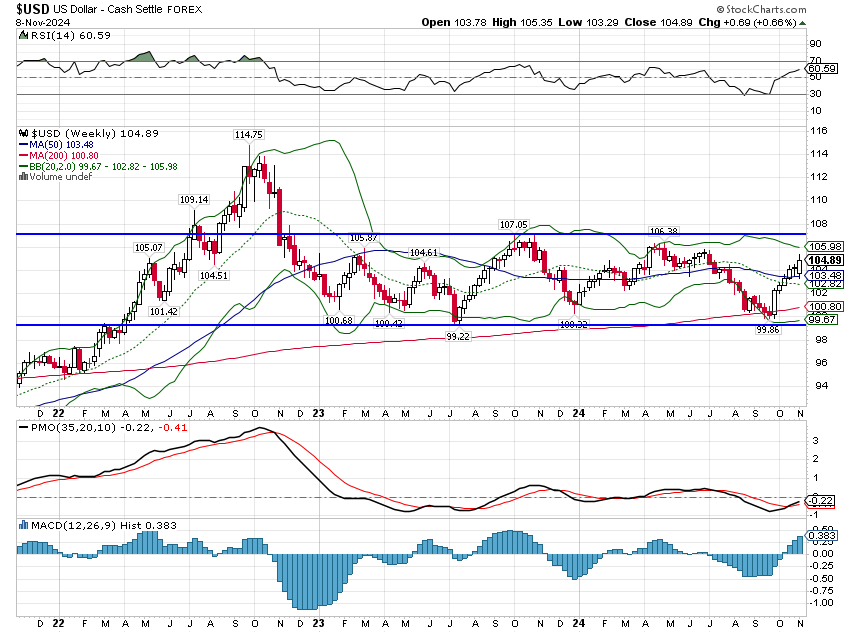

Environment

(Click on image to enlarge)

The outcome of the election did not, at least in the first few days, change the trend of the dollar or interest rates. The 10-year yield fell 6 basis points and the 2-year yield rose 4 basis points on the week. The result, a flatter yield curve, is putatively considered an indication of slower future growth but the change was too small to mean much.10-year TIPS yields also fell on the week and by more than the 10-year nominal bond. The change represents a fall in real growth expectations and a rise in inflation expectations. Again, though the changes here are very small so I wouldn’t read much into that just yet. As we get more detail about what the new administration will actually do versus what was promised on the campaign trail, the market will adjust.The dollar rallied in the wake of the election, as would be expected if the new Trump administration follows through with higher tariffs. In general, the country imposing tariffs sees its currency rise and the countries on which tariffs fall see their currency depreciate. That is the market’s way of offsetting the tariffs.These short term changes, for the dollar and interest rates, aren’t big enough to mean much but the directional changes are interesting, especially in light of the rally in stocks.The big picture, despite what many see as a big political change, didn’t change last week. The dollar and interest rates remain in their previous trading ranges with no real trend. In the chart above, we see a dollar and rates that are both rising over the 1 and 3-month periods but falling over the 6-month and 1-year periods. That is the very definition of trendless.(Click on image to enlarge)

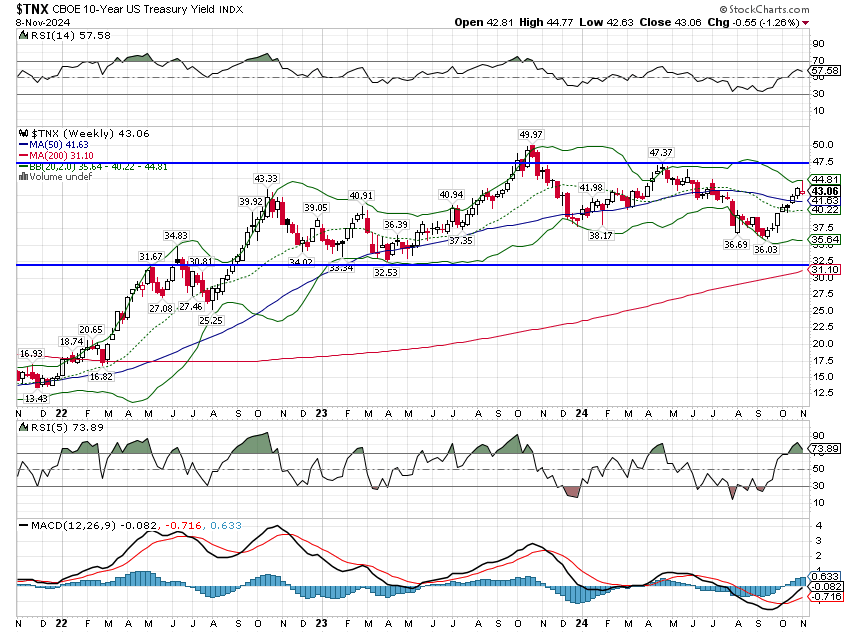

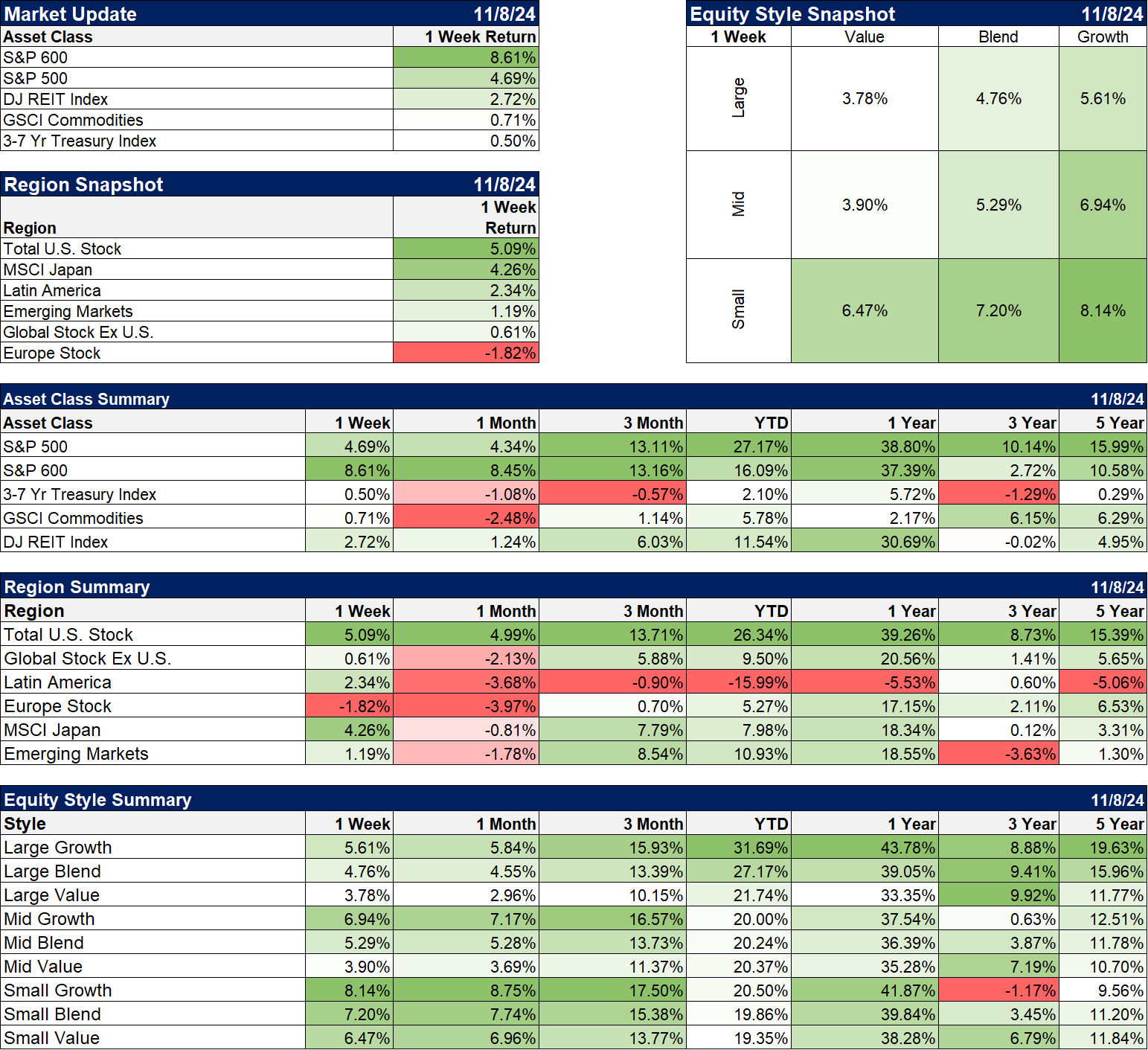

Markets

Stock investors obviously liked the election outcome with both large and small cap stocks rising significantly on the week. Small cap stocks did quite a bit better based on the idea that America behind a tariff wall will disproportionately benefit domestically-oriented small and mid sized companies. Small cap has now caught up to large cap over the last year although they still lag significantly over the last three years. More interesting to me is that bonds rallied on the news. If the stock market is right and an economic boom is on the horizon, bonds should have sold off. Did the bond market anticipate the Trump win while the stock market did not? I’m not sure that makes sense but I suppose it is possible. Another explanation could be that Trump will be great for profit margins but not overall growth, but again, I’m not sure that makes sense from an economic standpoint. Growth outperformed last week which is surprising and not. It’s surprising because growth stocks generally do well when growth is economic growth is scarce not when it is easily found (and the narrative is definitely that Trump is better for growth). On the other hand it makes sense in that Trump’s campaign was funded, to a large degree, by Silicon Valley which is ground zero for growth companies. Tesla wasn’t up 29% last week because Trump loves electric cars.Non-US stocks lagged in the wake of the election with Europe hurt the most. Draw your own conclusions on that one.(Click on image to enlarge)

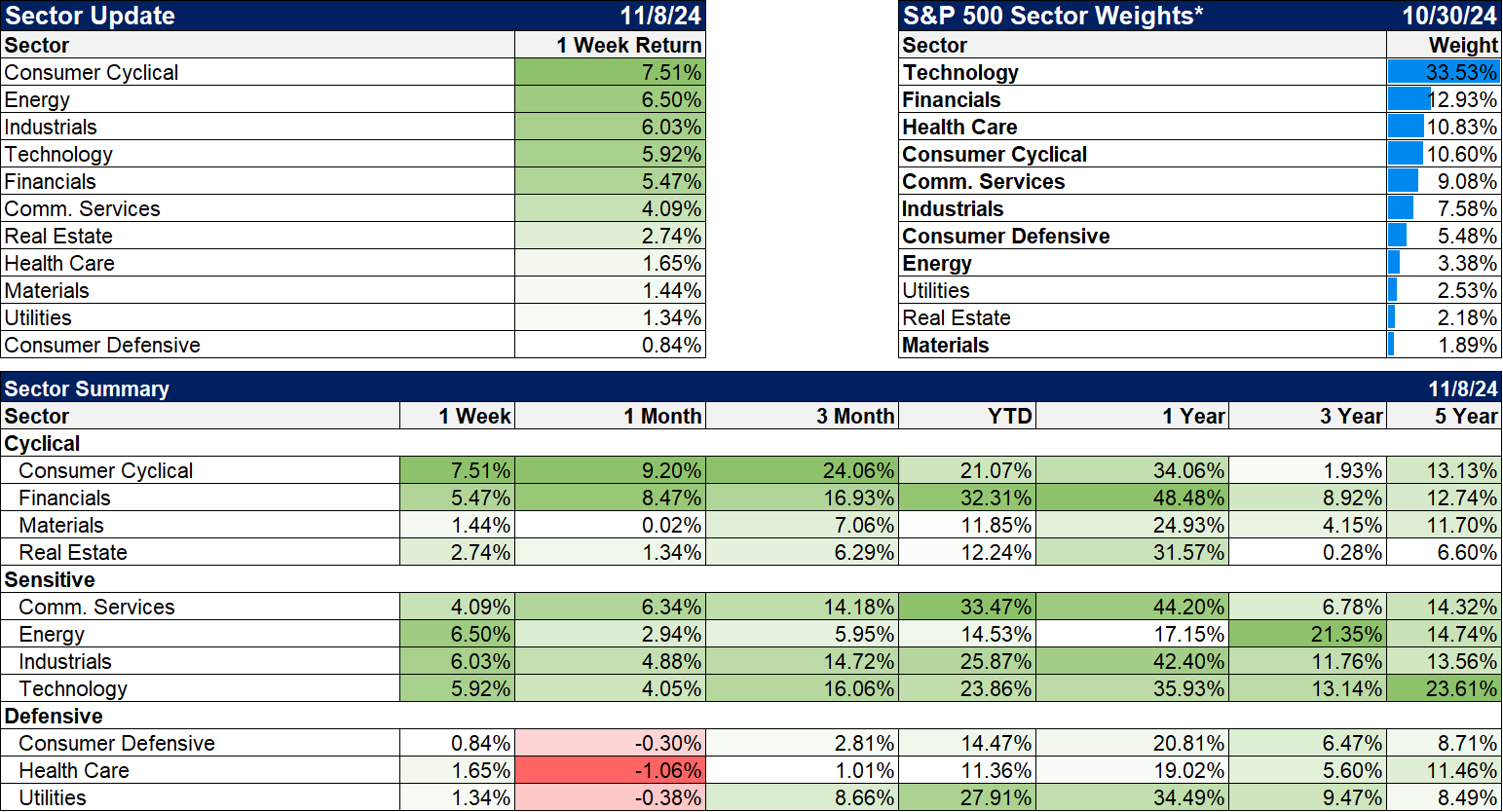

Sectors

On a sector basis the stock market’s expectation of higher growth is more obvious with economically-sensitive shares outperforming defensive shares.(Click on image to enlarge)

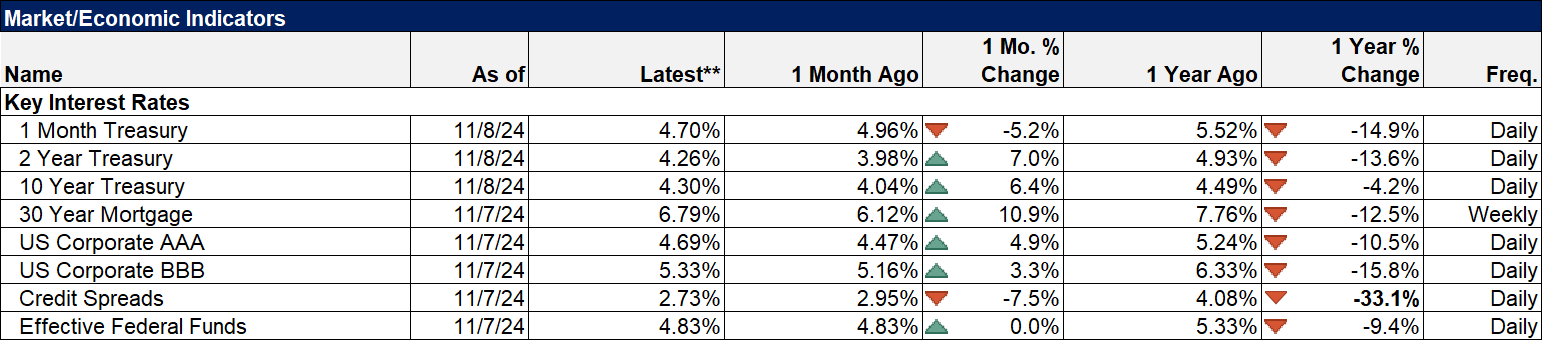

Economy: Market Indicators

Credit spreads are closing in on all time lows. Since 1997 the spread has only been narrower than the current 2.73% for six months. Five of those came in the summer of 1997 and the other month was May of 2007. There is essentially no reason at this point to own corporate bonds as an asset class.(Click on image to enlarge)

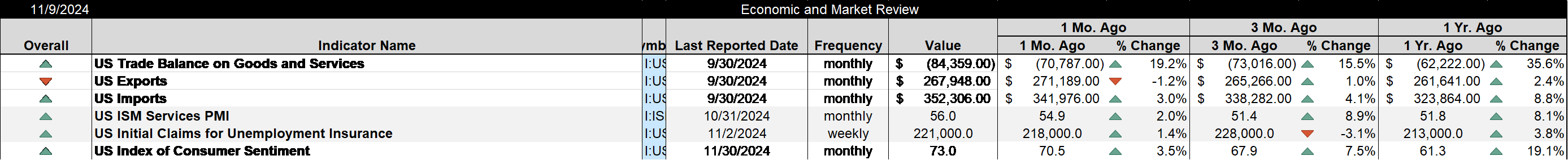

Economy: Economic Data

The economic data last week was pretty sparse. The trade numbers were largely as expected and probably irrelevant given the agenda of the incoming administration. The ISM services index hit 56, a very good level and up considerably from a year ago. Consumer sentiment improved somewhat but the survey was done before the election. Expect a big move up as Republicans’ mood improves.(Click on image to enlarge) More By This Author:

More By This Author: