<< Read More: The Eurodollar’s Soul; Part 1

The story of the asset bubbles is one of eurodollars alone. We can tell so much of the history of the past few decades by examining its pieces. The primary component has been derivatives, these financial instruments that are largely misunderstood shrouded often by what can appear to be incomprehensible complexity. That their own purveyors more often than not fall under that category explains a lot about the dizzying heights the eurodollar system achieved, and now its unending global economic drag. Combined with visible ignorance and arrogance on the part of policymakers, the whole story is neatly documented on both sides of the permanent crisis divide.

In September 2014, much of the mainstream was sublimely confident that the cusp of recovery was no longer some theoretical condition. It was truly believed at hand, in no small part because that was what everyone was saying, including all the right people. Among them were banks that outwardly were at least as cautiously optimistic as Fed officials. Some banks, however, were more than that. The chief example was Deutsche Bank, but that institution was not alone.

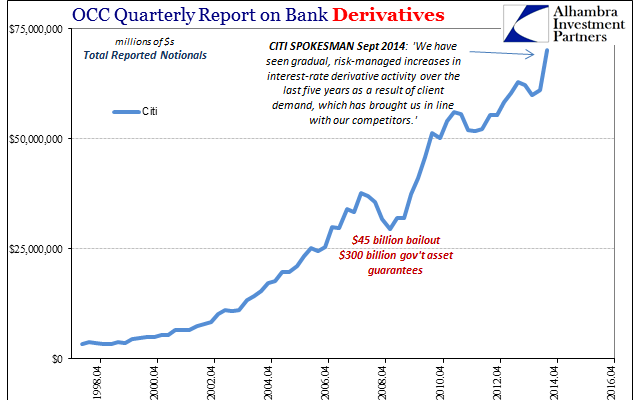

Citigroup was in an unusual position at that time. In the US, it had received the largest bailout by far, appreciating in late 2008 $45 billion in direct government investment along with more than $300 billion in asset guarantees just to keep the bank afloat to see 2009. From almost the moment of its public sector rescue, it alone among American banks started to bet heavily again, at least in terms of its derivative book.

According to call reports filed with the Office of Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the sum of all its derivatives contracts had declined to a low point of $29.6 trillion (gross notionals) in Q1 2009 – the moment of the government’s deepest involvement. That was down 21% from a peak of $37.7 trillion in Q1 2008, the usual apex we find around Bear Stearns’ liquidity stumble into a troubling merger.

By the time of the 2011 crisis, Citi had far surpassed that level betting heavily, it seems, on the success of QE1 and then QE2 to the lead the world and the global money system back to its pre-crisis glory. Despite the setback in the summer of 2011, the bank’s activities continued to surge so that by September 2014, under the auspices of QE3, Citi had actually taken the derivative crown from JP Morgan.