The ECB is currently in the process of designing a fresh €500bn securities purchase program. There are multiple options on the table and the central bank is having staff run through a number of scenarios. Asset classes and asset quality scenarios run the gamut – from AAA assets only to everything from BBB- and up. The possibilities include government bonds only as well as a mix that also contains private credit. This is all in addition to the ABS and covered bond buying programs already in place.

But here comes the tough part – risk sharing. The ECB is looking at three possibilities:

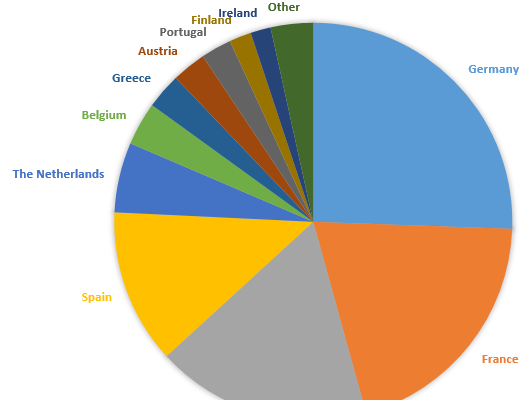

Method-1. The full amount of securities purchased is shared based on each member-state ownership of the ECB (capital subscriptions). This is how risk has been shared so far on purchases by the central bank. It would be similar to the so-called Securities Market Program (SMP), which is how the ECB originally got stuck with defaulted Greek debt. Of course the Germans, with their 26% exposure to the ECB, are quite unhappy about this.

Â

Method-2. Another option on the table is to run bond purchases similarly to the so-called emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). In such a program “any costs of, and the risks arising from, the provision of ELA are incurred by the relevant NCB” (NCB stands for National Central Bank, such as the Bank of Italy for example). In such structure, each NCB would buy some prescribed amount of its nation’s government bonds and assume all the risk of these purchases. Thus the Bank of Italy, not the ECB, would assume all the risk for Italian government bonds it purchases via this program.

While this option would appease Germany, such action would edge closer to a decentralized Eurozone, risking the disintegration of the monetary union. At the same time it also doesn’t completely segregate the risk because many periphery NCBs owe the Eurosystem money via TARGET2. That means if one of the NCBs becomes insolvent due to an over-concentrated exposure to its national bonds, it could still be damaging to the ECB’s stakeholders.

Method-3. The third option would apply Method-1 of risk sharing (above) up to some amount of purchases (let’s say the first €250bn), after which the ECB reverts to Method-2 (above) for the remaining purchases.

At this point it’s all about picking the “lesser evil”. Any large government bond purchase program in the euro area creates a moral hazard, removing the incentives for fiscal discipline. With interest rates at historical lows driven by central bank purchases, politicians are likely to institute new spending programs – such as the ones that brought about the Eurozone crisis.

Nevertheless the ECB has little choice at this point as deflation knocks at the door. The area’s CPI is now in the red (and France is expected to be there shortly), while longer dated inflation expectations are collapsing.