Given that today started with a review of the “dollar†globally as represented by TIC figures and how that is playing into China’s circumstances, it would only be fitting to end it with a more complete examination of those. We know that the euro-dollar system is constraining Chinese monetary conditions, but all through this year the PBOC has approached that constraint very differently than last year.

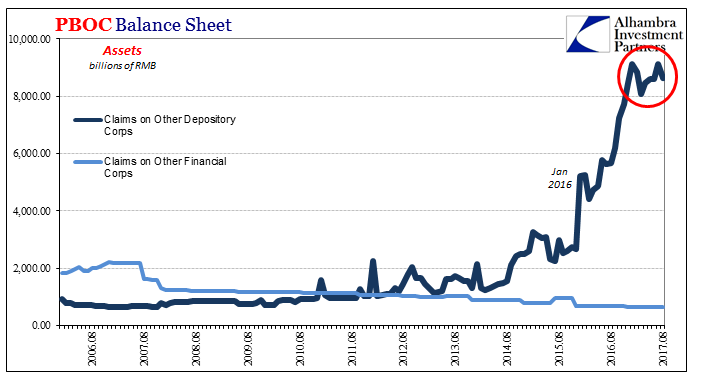

The updated balance sheet numbers through August show that unlike in the second half of 2016 China’s central bank in 2017 is very reluctant to increase the RMB portion of its balance sheet. The vast majority of its assets are forex, but those continue to fall (the subject of that earlier TIC investigation).

In January 2017, the PBOC had allowed largely the biggest banks to borrow RMB 9.1 trillion through its various liquidity programs. Given that the central bank had ended 2015 with only RMB 2.7 trillion in balances, that was an enormous liquidity program (at least on its own terms) to be conducted condensed to just over one year’s time.

The question has been why monetary authorities stopped. The mainstream view is that policy has shifted to tightening. That is the effect, not the reason. It is supposed to be restraint in the name of bubbles and getting control of them, but instead it works out in economic growth to the same problems as the past few years.

Bubbles aren’t the immediate issue, FAI is and always will be. The economy in China reflects monetary restraint which cannot be separated from that overriding “dollar†constraint. The simple fact is that RMB bank reserves are not growing near fast enough to support economic momentum.

Because the PBOC is restraining itself in RMB this year, it has left the big banks to depend more on deposit creation and less on interbank activities – including their forwarding of surplus liquidity into repo and unsecured interbank markets.