Seven central banks around the world have lowered the interest rate that they use to implement monetary policy to a negative rate: along with the very prominent European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, the others include the central banks of Bulgaria, Denmark, Hungary, Sweden, and Switzerland. How is this working out? When (not if) the next recession  hits, are negative interest rates a tool that might be used by the US Federal Reserve? The IMF has issued a staff report on “Negative Interest Rate Policies–Initial Experiences and Assessments” (August 2017). In the Summer 2017 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Kenneth Rogoff explores the arguments for negative interest rates (as opposed to other policy options) and practical methods of moving toward such a policy in “Dealing with Monetary Paralysis at the Zero Bound” (31:3, pp. 46-77).

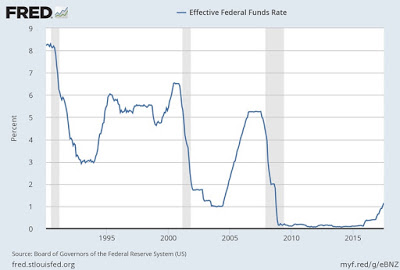

When (and not if) the next recession comes, monetary policy is likely to face a hard problem. For most of the last few decades, the standard response of central banks during a recession has been to reduce the policy interest rate under their control by 4-5 percentage points. For example this is how the US Federal Reserve cut it interest rates in response to the recessions that started in 1990, 2001, and 2007.

Â

The problem is that when (not if) the next recession hits, reducing interest rates in this traditional way will not be practical. As you an see, the policy interest rates has crept up to about 1%, but that’s not high enough to allow for an interest rate cut of 4-5% without running into the “zero lower bound.”

The problem of the zero lower bound seems unlikely to go away. Nominal interest rate can be divided up into the amount that reflects inflation, and the remaining “real” interest rate–and both are low. Inflation has been rock-bottom now for about 20 years, even as the economy has moved up and down, leading even Fed chair Janet Yellen to propose that economists need to study “What determines inflation?” Real interest rates have been falling, and seem likely to remain low. The Fed is slowly raising its federal funds interest rate, but there is no current prospect that it will move back to the range of, say, 4- 5% or more. Thus, when (not if) the next recession hits, it will be impossible to use standard monetary tools to cut that interest rate by the usual 4-5 percentage points.

What macroeconomic policy tools will the government have when (not if) the next recession hits. Fiscal policy tools like cutting taxes or raising spending remain possible, although with the Congressional Budget Office forecasting a future of government debt rising to unsustainable levels during the next few decades, this tool may need to be used with care.  Hitting the zero bound is why the Fed and other central banks turned to “quantitative easing,” where the central bank buys assets like government or private debt, although this raises obvious problems of what assets to buy, how much of these assets to buy–and the likelihood of political intervention in these decisions.

Thus, some central banks have taken their policy interest rates into negative territory. As the figure shows, the Bank of Denmark went negative in 2012, while a number of others did so in 2014 and 2015.