When Japan’s call rate (the nominal rate from their central bank) went to the zero lower bound, Japan developed deflation. It was not a deflation where the bottom fell out and kept falling. It was a deflation somewhat stable below 0%. The stability of their low deflation would make sense according to the Fisher Effect that describes a situation where inflation moves to a stable rate determined by the call rate minus the real growth in output.

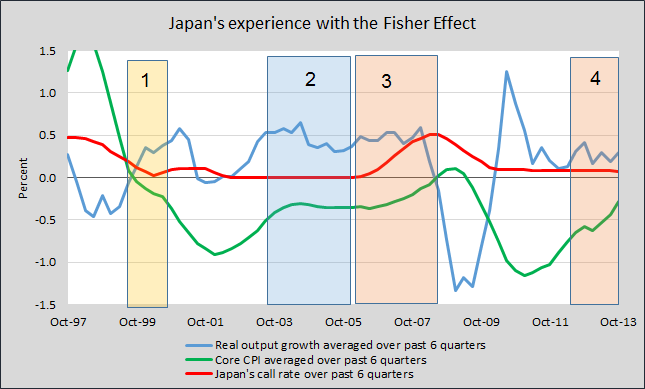

Here is a graph of the 3 determinants for the Fisher Effect in Japan since 1997.

- The call rate (nominal interest rate from Japan’s central bank), averaged over past 6 quarters.

- Core CPI less food and energy, averaged over 6 quarters.

- Real GDP output growth, averaged over 6 quarters.

The Fisher Effect equation for Japan is…

Core CPI inflation = Call rate – real output growth

In zone #1, the call rate had reached the zero lower bound and inflation was falling into deflation. If you look close, the deflation was beginning to slow down it’s descent toward the rate where the Fisher Effect would point to, namely around -0.3%. Then the recession of 2001 hit and deflation kept falling. (Note: If inflation is low at the start of a recession, it can turn into deflation.)

In zone #2, Japan’s economy began to level out after the effects of the 2001 recession. Real output growth settled in at around 0.4% with the call rate sitting very near 0%. The Fisher Effect would say that inflation would then stabilize at -0.4%. The green line of inflation shows us that inflation did in fact settle into a rate around -0.4%.

In zone #3, the call rate (red line) began to rise at roughly the same rate as inflation (green line), which agrees with the Fisher equation. When real output is steady, inflation and the nominal rate rise in sync. Eventually the call rate rose to exactly the rate of real output growth (blue line). According to the Fisher Effect, inflation would then rise to around 0% (call rate – real output growth). We see that inflation was in fact rising toward 0%. Then real output began to drop and inflation kept rising. This also makes sense according to the Fisher Effect, where a lower real output growth at a constant call rate would lead to higher inflation. But then soon after the 2008 crisis hit and other more powerful factors interrupted the process.