Though we may think of modern economies as being modern and perhaps disassociated with some of the more primitive aspects of the past, there remain to this day seasonal fractures in economy and finance. When the Federal Reserve was created in 1913, for example, its first task was “currency elasticity†which may not have been what we think about as it is today (subscription required).

The Fed was never meant to countermand them, rather its task was simply to reduce the chances that seasonal flows would lead to the worst circumstances. After all, though bank panics and depressions were a relatively new phenomenon in the 19th century, it didn’t take any sophisticated analysis to realize that seasonal flows of gold and currency often played a large role in them. Economic calamity always seemed to strike when the monetary system was at its weakest (October).

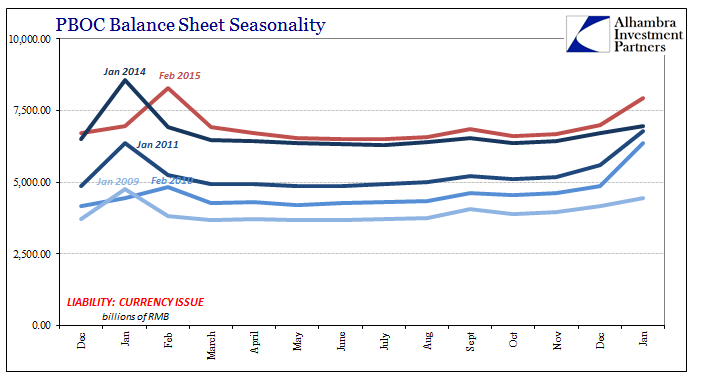

Just as the US economy revolves seasonally around Christmas shopping, the Chinese economy gives prominence to the Lunar New Year. With the whole country closed for a full (Golden) week each year, the Chinese central bank undertakes conspicuous liquidity measures to ensure ample currency available to the real economy. Since the holiday itself is not attached to a specific calendar date, there is some variance as to when the PBOC begins and ends those programs.

Chinese currency is as US currency, at least dollars rather than “dollarsâ€, a liability of the central bank. To create and float more currency any central bank will either have to expand in assets or redistribute liabilities. For the most part, China’s currency volume surrounding its holidays is and has been a very easy affair. In any given year, it is a flat level with a minor rise in September in anticipation of China’s other Golden Week. The major action is typically January or February, with some years receiving a small anticipatory rise of currency the preceding December.

With more currency in circulation, there is typically reduced demand for bank reserves. In December 2013, for example, the PBOC boosted Chinese bank reserves by nearly RMB 800 billion in preparation for the New Year, which fell on January 31 that year. During January 2014, bank reserves dropped back by more than RMB 400 billion while total currency increased sharply by RMB 2.08 trillion. The PBOC accommodated that large currency supply with an almost as large increase in its total balance sheet size (both currency and asset-side liquidity measure were withdrawn in February 2014).