EU politicians may have recently watered down their ambitions to reduce plastic demand, but the continent’s petrochemical producers are still having a torrid time. It’s a perplexing environment which doesn’t give us much hope that we’re going to see speedy progress towards ‘greener’ plastics anytime soon.

It’s hard to green plastic production in Europe when the going gets tough

Producers of plastics are facing very ambitious carbon emission reduction targets for their European sites. They fall under the European Emission Trading Scheme where, according to the current setup, CO2 allowances are phased out by 2040. From then on, plastic producers in Europe will not be allowed to emit CO2 into the atmosphere on ‘a net balance’, so they no longer contribute to global warming.Luckily, there are technologies available to lower emissions by up to 75%, but they come at a serious cost, according to :

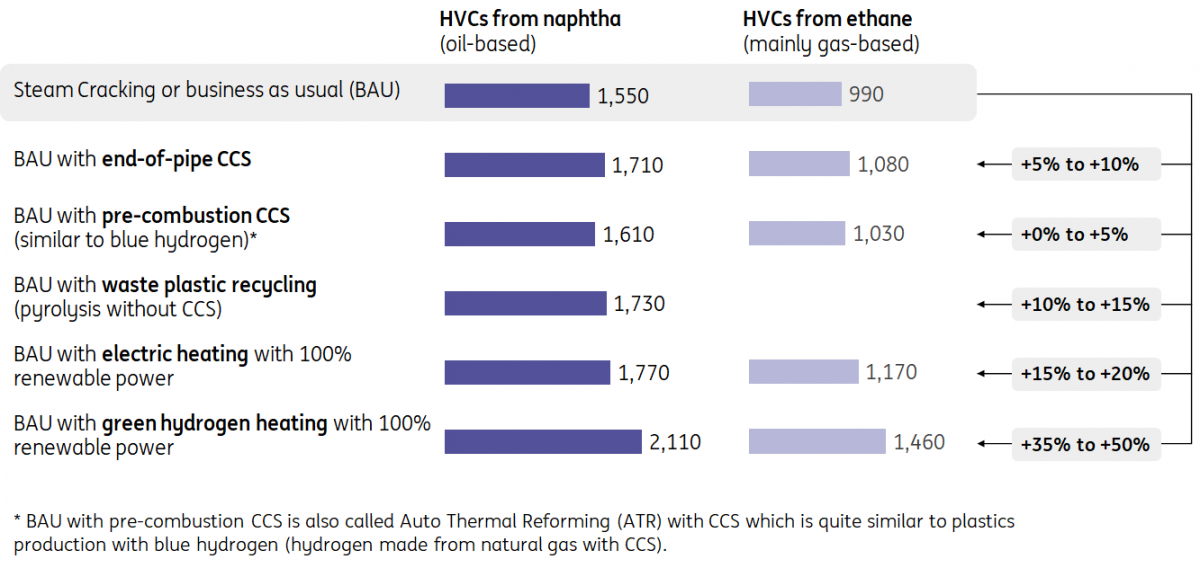

The irony is that a 50% higher price for a plastic bottle would barely increase the price you pay for your favourite soft drink. Consumers are likely to keep buying them; we most likely will, and our teenage kids almost all certainly do.Such a cost increase is a big deal for plastic producers in Europe, who play a small part in the entire supply chain and cannot charge consumer prices. In fact, they operate in international and highly competitive markets with little room to fully pass on higher production costs.Greening oil & gas-based plastics is up to 50% more expensive; carbon capture and storage (CCS) is cheap; green hydrogen still expensiveIndicative costs for different oil-based plastics (naphtha) and gas-based plastics (ethane) in euros per ton High Value Chemicals (HVC)(Click on image to enlarge) ING Research based on IEA, BNEF, Dechema, TNO, PBL, CE Delft and McKinsey.Costs are calculated from a North-Western European perspective and based on many economic and chemical assumptions. We list our main economic assumptions here: a gas price of €55/MWh, a power price of €125/MWh, a carbon price of €85/ton with full carbon pricing (no free allowances), Naphtha price of €620/ton, an ethane price of €375/ton and a price of €6/ton for plastic waste to produce pyrolysis-oil in the process of chemical recycling. Note that pyrolysis yields naphtha, but hardly any ethane, so it is not a solution to produce ethane. Further note that these energy prices represent spot and future prices for 2023 and 2024 in the Northwest European energy market as of early November 2023. We have applied technology costs between €2,450 to €3,200/tonHVC for naphtha steam cracking and €1,850 to 2,350/tonHVC for ethane steam cracking, with the low values for the business-as-usual case (steam cracking) and the higher values for steam cracking with pre combustion CCS and for pyrolysis. We have assumed CCS capex of €150/ton and the CCS capture rate is set at 85% for pre-combustion CCS and 75% for post-combustion CCS. We apply a Western made alkaline electrolyser that costs around 1,000€/kW and runs with an efficiency of 70% and capacity rate of 70%. This results in green hydrogen costs around €7/kg at market power prices of €125/MWh. We have converted all dollar-prices using an exchange rate of 1$=0.94. The discount rate is set at 8%, inflation on operational expenses (OPEX) at 3%. In practice, all these input variables show considerable variation which yields a wide range of outcomes for every technology. We have chosen to present point estimates as they often capture the main insights better than wide ranges. Treat these numbers as indicative outcomes around which real time projects will vary.

ING Research based on IEA, BNEF, Dechema, TNO, PBL, CE Delft and McKinsey.Costs are calculated from a North-Western European perspective and based on many economic and chemical assumptions. We list our main economic assumptions here: a gas price of €55/MWh, a power price of €125/MWh, a carbon price of €85/ton with full carbon pricing (no free allowances), Naphtha price of €620/ton, an ethane price of €375/ton and a price of €6/ton for plastic waste to produce pyrolysis-oil in the process of chemical recycling. Note that pyrolysis yields naphtha, but hardly any ethane, so it is not a solution to produce ethane. Further note that these energy prices represent spot and future prices for 2023 and 2024 in the Northwest European energy market as of early November 2023. We have applied technology costs between €2,450 to €3,200/tonHVC for naphtha steam cracking and €1,850 to 2,350/tonHVC for ethane steam cracking, with the low values for the business-as-usual case (steam cracking) and the higher values for steam cracking with pre combustion CCS and for pyrolysis. We have assumed CCS capex of €150/ton and the CCS capture rate is set at 85% for pre-combustion CCS and 75% for post-combustion CCS. We apply a Western made alkaline electrolyser that costs around 1,000€/kW and runs with an efficiency of 70% and capacity rate of 70%. This results in green hydrogen costs around €7/kg at market power prices of €125/MWh. We have converted all dollar-prices using an exchange rate of 1$=0.94. The discount rate is set at 8%, inflation on operational expenses (OPEX) at 3%. In practice, all these input variables show considerable variation which yields a wide range of outcomes for every technology. We have chosen to present point estimates as they often capture the main insights better than wide ranges. Treat these numbers as indicative outcomes around which real time projects will vary.

The outlook for European producers appears bleak

Given the higher costs, greening plastic production would be a challenge even in good times. But unfortunately, times are far from good. Earlier this year, announced it would cut its investment budget amid the downturn. And influential Bloomberg analyst Javier Blas recently even warned that Europe’s petrochemical industry is heading for . In his words:“Europe’s consumption of naphtha, the cornerstone of the petrochemical industry which produces plastics, will drop in 2023 to a nearly 50-year low, down 40% from its all-time peak. As a result, the industry’s workhorses, called steam crackers, are operating at uneconomical rates between 65% to 75% of their capacity. Because of enormous fixed costs, anything below 90% is a source of concern; 85% is bad, and below 80% is seen as catastrophic.”We don’t think that petrochemical companies in Europe will face an existential threat as many are multinationals which can shift production to other sites outside Europe, at least to some degree. However, Blas does have a point that the outlook for production at European sites is far from optimistic.Given the higher costs of greener plastics and the tough economic environment, it is hard to see very fast sustainable progress on the supply side. One could argue that this is irrelevant as Europe’s Emissions Trading scheme forces petrochemicals to reduce emissions anyway, provided that politicians do not weaken the scheme. If emissions can’t be reduced enough through cleaner production, plastic production must be lowered to meet the ETS emission targets. Lower output could be seen as a degrowth policy, a concept that is gaining importance in the economic and climate literature. But it goes against recent trends in Germany and France that want to protect their energy-intensive industries, not only in helping them to become green, but also to protect production and jobs and to increase strategic autonomy.The fact that petrochemicals do not fall under the carbon border adjustment mechanism yet does not help either. So their activities in Europe are not protected from imported plastic of which the CO2 footprint is often higher. And they struggle to export plastic as before as their competitiveness has been damaged despite the lower footprint.

Politicians are not overly ambitious on the demand side

With reduced optimism on the supply side, politicians could play a firm role by reducing plastic demand. But here, too, there’s room for less optimism as the European Parliament in November its packaging waste law following political division and intense lobbying.Overall, the new law wants to cut the amount of plastic in Europe by 10% by 2030, 15% by 2035 and 20% by 2040. In Western Europe, the average annual plastic consumption is around 150 kilograms per person, which is more than twice the global average of 60 kilograms. So, Europeans would still consume 120 kilograms of plastic by 2040 if the target were to be met. That is still an awful lot.The law includes some specific measures to reduce plastic packaging, including a ban on very lightweight plastic carrier bags (unless required for hygiene or preventing food waste) and heavy restrictions on single-use formats like miniature hotel toiletries.But during the negotiations, measures to reduce plastic packaging waste, such as bans on unnecessary or single-use plastics, for things such as fruit and vegetables, for instance, were removed. Reuse targets were also watered down. One could question whether the 20% plastic reduction target can be met without strong demand reduction policies. As green lawmaker Grace O’Sullivan said, “we cannot recycle our way out of this mess.”

An ongoing conundrum

We see petrochemicals are struggling with their European sites. On the one hand, they need to cut costs to stay competitive. On the other, they need to invest heavily in greener production methods, which in practice often means major and costly overhauls. We are talking multi-million euros investment at best, in some cases multi-billion numbers. How this plays out is still a conundrum for us, as there are no easy and quick solutions. Energy costs are likely to stay higher for longer in Europe, so any hope of any quick relief is premature. However, the CO2 cap from the emissions trading scheme is lowered significantly every year, pushing for greener production provided that companies and politicians want to keep production in Europe.And let’s not forget that European politicians are not overly ambitious to reduce plastic demand. So, all in all, we have become less optimistic about fast progress towards greener plastics in Europe.More By This Author: