That’s the title of a new European Central Bank working paper (coauthored with Yin-Wong Cheung (City U HK), Antonio Garcia Pascual (Barclay’s), and Yi Zhang (U. Wisc.)) just released.

(Click on image to enlarge)

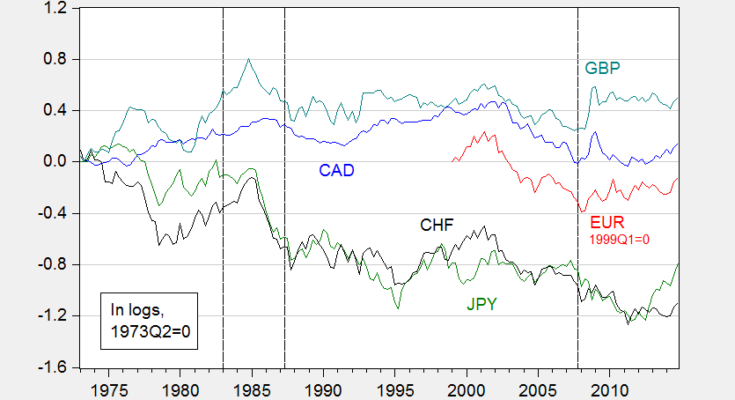

Figure 1:Â Log nominal exchange rates against USD (1973Q2=0), up denotes appreciation of USD. Dashed lines denote start of out-of-sample forecasting periods I, II, III.

From the summary:

Previous assessments of nominal exchange rate determination, following Meese and Rogoff (1983) have focused upon a narrow set of models. Cheung et al. (2005) augmented the usual suspects with productivity based models, and “behavioral equilibrium exchange rate†models, and assessed performance at horizons of up to 5 years. In this paper, we further expand the set of models to include Taylor rule fundamentals, yield curve factors, and incorporate shadow rates and risk and liquidity factors. The performance of these models is compared against the random walk benchmark. The models are estimated in error correction and first difference specifications. We examine model performance at various forecast horizons (1 quarter, 4 quarters, 20 quarters) using differing metrics (mean squared error, direction of change), as well as the “consistency†test of Cheung and Chinn (1998). No model consistently outperforms a random walk, by a mean squared error measure, although purchasing power parity does fairly well. Moreover, along a direction-of-change dimension, certain structural models do outperform a random walk with statistical significance. While one finds that these forecasts are cointegrated with the actual values of exchange rates, in most cases, the elasticity of the forecasts with respect to the actual values is different from unity. Overall, model/specification/currency combinations that work well in one period will not necessarily work well in another period.

It’s important to know that we are not trying to out-forecast in real time a random walk. Rather, we use out-of-sample forecasting (sometimes called an ex post-historical simulation) to guard against data mining and to highlight which models have the most empirical content. An earlier version of the paper is discussed in this post.