Raise your hand if this sounds familiar: markets are calm, things are stable, stocks are levitating on virtually no volume… and suddenly there is a price ‘air pocket’Â as one or more assets unexpectedly plunge in what has become a now daily “flash crash” du jour, traders panic, unable to front-run orderly traffic HFTs immediately shut down, and all hell breaks loose.

We expect everyone to have gone through this “local tail” event scenario at least once and likely many times, one which we predicted would become the norm back in 2009, and one which has, as of 2015, become the norm.

Thank the Fed.

But don’t take it from a “fringe, tinfoil hat, conspiracy theory” website which has been repeating this for so many years we have to dig deeper with every passing day to keep ourselves amused at this farce: here is Bank of America’s head of global equity derivatives research, Benjamin Bowler, with a piece slamming the massively manipulated “market” that 7 years of global central bank intervention has created, and a simple schematic which demonstrates just how broken everything is, and why one should expect many, many more such “local tail” freakouts in the future.

From Bank of America

Central bank’s risk manipulation well explains local tails

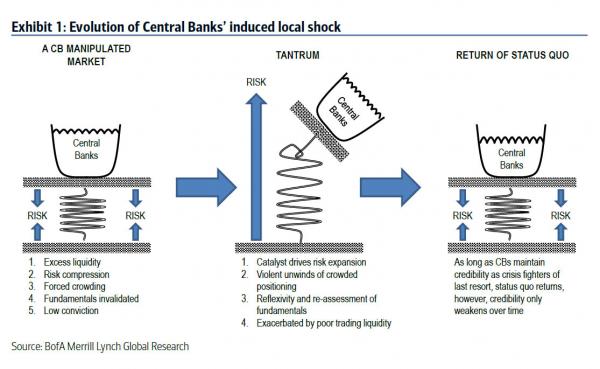

A good way to explain why we have seen local tail risks arise so frequently since central banks began to heavily manipulate asset prices is with the following analogy, illustrated in Exhibit 1. Essentially central banks, by unfairly inflating asset prices have compressed risk like a spring to unfairly tight levels. Unfortunately, the market is aware the price of risk is not correct, but they can’t fight it, and everyone is forced to crowd into the same trade. By manipulating markets they have also reduced investors’ inherent conviction by rendering fundamentals less relevant.

This then creates a highly unstable (fragile) situation that breaks violently when a sufficient catalyst causes risk to rise – overly crowded positioning meets a market with little conviction.

Catalysts can range from a “valuation scare†similar to Oct-14 or Aug-15 to a prominent investor stating that assets (e.g. bunds) are not fairly priced and are the “short of the centuryâ€.

The unwinds from these crowded positions are violent, but almost equally violent in some cases are the reversals, which are driven from investors crowding back in when they realize central banks are still there providing protection.

From this vantage point, it becomes clear that the biggest visible risk to financial markets is a loss of confidence in this omnipotent CB put.