In principle, there is absolutely nothing wrong with derivatives. They serve a valuable function, by transferring risk from those who don’t want to be exposed to it to those who are willing to take risk on in their stead for a fee. However, since the adoption of the pure fiat money system, credit growth has literally gone “parabolic†all over the world. This growth in outstanding credit has been spurred on by interest rates that have been declining for more than three decades.

Larger and larger borrowings have become feasible as the cost of credit has fallen, and this has in turn spawned an unprecedented boom in financial engineering.

When critics mentioned in the past that this had created systemic dangers, their objections were always waved away with two main arguments: firstly, the amount of net derivatives exposure is only a fraction of the outstanding gross amounts, as so many contracts are netted out (i.e., things are not as bad as they look). Secondly, the system had proven resilient whenever financial system stresses occurred. Perhaps not as resilient as it seemed, considering that these crises as a rule required heavy central bank interventions and/or bailouts in various shapes and forms. Would the system have been as resilient if those had not occurred? We have some doubts with regard to that.

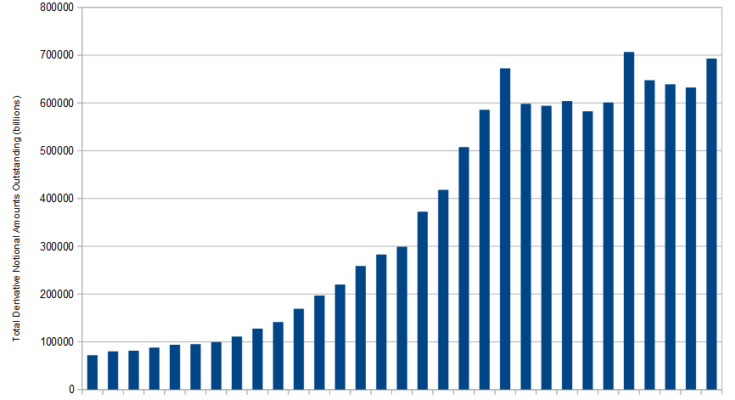

Since the crisis, derivatives growth has stalled, but the notional amount has returned to its record highs as of the end of 2013 – click to enlarge.

Â

Then came the 2008 crisis, which underscored that the critics had actually been right about a major point: the system depends on almost everybody in the chain performing. It doesn’t matter if one holds a contract that is in theory netted out if one party to it fails to pay up. One of the reasons why AIG was bailed out (or rather, its creditors were), was no doubt that the authorities feared that the failure of such a large player could snowball into cascading cross-defaults, and completely shatter trust in the system’s “resilienceâ€.

We still remember a few funny anecdotes that preceded the actual crisis point. One was that Fannie Mae – the eventual bankruptcy of which was predicted by Doug Noland almost a decade before it happened – had to hire some 2,000 outside accountants to sort out its more than 20,000 different derivatives positions, over which no-one at the firm had any overview anymore. The accountants were at work for at least half a year if memory serves.

Another was when AIG’s board first realized it had a problem with its CDS positions in early 2008. What was so hilarious was that while they were already in the hole by billions at the time, they couldn’t tell by how many. The board erroneously concluded that while the insurance giant was wounded, it was not mortally wounded. This view was revised rather dramatically within three months of the comical press release in which it was announced that the board didn’t really know how big AIG’s mark-to-market loss was (it was clear though that it kept growing by the day).

Picking Up Pebbles in Front of a Steamroller

AIG’s experience is relevant insofar, as the institution was in fact “picking up pebbles in front of a steamrollerâ€. It had a star trader in London by the name of Joe Cassano, who was in charge of the CDS business. He must have figured that since AIG was an insurer, writing insurance was what it should do. The problem was that at the height of the Greenspan policy inspired real estate and mortgage credit bubble, everything seemed to be perfectly fine with the world. Credit spreads were tight; junk bond yields were at record lows; structured credit products backed by NINJA mortgages of the sub-prime and ‘Alt A’ variety were stable and sought after. There was no volatility, and no volatility premiums. So the only way to make serious money was by making it up with volume. If one can sell a 5 year CDS at 50 basis points, one needs to sell sizable volumes to actually make enough money to earn a big bonus (e.g. 5 year CDS on Greek debt once traded just above 30 basis points in 2007. They went out at over 26,000 bps. just before the underlying debt was PSI’d).