As the new year is upon us, investors are going to hear a lot about central bank policy and the future of interest rates. Wall Street, in particular, has had a dismal forecasting record, consistently over-estimating 10- year bond yields. What happens so often is that the forecasters do not adequately account for the current state of interest rates. Rather, forecasters express their wishes for the coming year without an appreciation of what lies behind the current level of rates. This blog looks at the relationship between current rates and expected rates and what we might deduce regarding where interest rates are heading in the coming year.

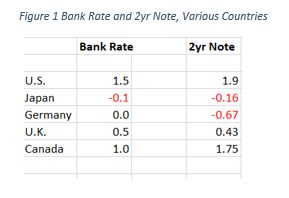

To begin, a comparison of central bank policy rate, e.g. Fed funds rate, with the 2yr note provides some clues as to what the market is expecting in the short run (Figure 1):

- United States. The U.S. 2yr note is anticipating a couple of rate hikes over the next two years, moving the Fed funds rate to 2%;

- Germany and Japan. These central banks continue to lend at zero rate and their 2-year notes do not anticipate any change in that policy; in fact, their 2-year rates suggest investors are content with earning negative returns in exchange for the safety of owning government debt for two years;

- United Kingdom. The U.K.’s market for bonds is highly influenced by the uncertainty regarding the Brexit negotiations and its impact on sterling’s value; overall, investors do not see the bank rate changing; and,

- Canada. Recent rate hikes by the Bank of Canada have encouraged bond investors to push up the yield on 2 -year notes, anticipating three additional rate hikes in 2018; I have argued that the economic data don’t support this interest rate outlook in an earlier blog.[1]

While central bankers can have direct impact on the very short-term market (less than 24 months out), they have virtually no control over long rates. Long rates are tied closely to: (1) expected inflation and (2) risk premiums.