During the late 1770s, a newly founded United States began to run up significant debts to finance the American Revolution. With limited access to credit and little to no tax base, the Continental Congress issued the Continental to finance the war. But by the end of the decade, inflation was nearly 50 percent, a suit cost a million Continentals, and the phrase “not worth a Continental†had entered the national lexicon. With the help of our fourth U.S. president, James Madison, we review why the Continental experiment ended so badly.

Financing the Revolution

Readers of this series are by now familiar with the ever-changing link between the financing of wars and the rise of financial crises. First in the series, we covered theKipper und Wipperzeit coin clipping crisis that was in part a result of struggles to pay for the Thirty Years’ War. A subsequent post noted that the monetary contraction caused by the Not So Great Re-Coinage of 1696 inhibited Britain’s ability to pay the armies engaged in the Nine Years’ War. Later, we examined how the Seven Years’ War led to a commodity boom, then the sudden crash of 1763.

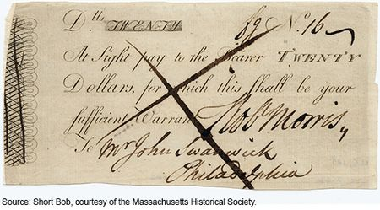

At the onset of the American Revolution, the Continental Congress recognized that to effectively control the revolution, they would have to finance it. But the means of finance available to established nations, like access to credit and taxation, weren’t so readily available. The Continental Congress was reluctant to rely on taxation to fund the revolution, given the role of taxes in bringing on the war in the first place. Despite loans from France, the credit risk of additional loans to support a colonial rebellion without a reliable tax base seemed too high to most investors. Gold and silver coins had for years been flowing to Britain for purchases and they remained in such short supply that colonial trade was largely based on agricultural credit, as we noted in our last piece on thecommodity crisis of 1772. But prior to the revolution, some colonial states with a strong tax base like New York and Pennsylvania had success with paper currency. So Congress turned to the printing press as the next best option to finance the revolution, and began issuing Continentals by mid-1775.