The membership drive and subsequent launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has been a favorite topic of ours since the UK threw its support behind the China-led venture in March.

London’s move to join the bank marked a diplomatic break with Washington, where fears about the potential for the new lender to supplant traditional US-dominated multilateral institutions prompted The White House to lead an absurdly transparent campaign aimed at deterring US allies from supporting Beijing by claiming that the AIIB would not adhere to international standards around governance and environmental protection.Â

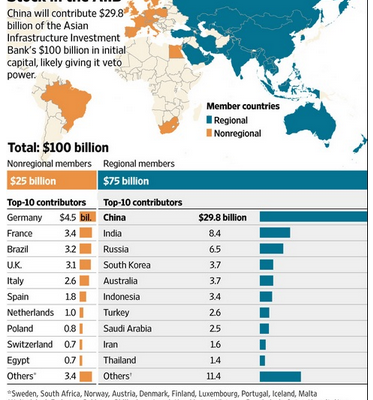

In the weeks and months following the UK’s decision, dozens of countries (including many traditional US allies) expressed interest in the new lender and by the time the bank officially launched late last month, the US and Japan (who dominate the IMF and ADB, respectively) were the only notable holdouts.Â

As we never tire of discussing, the reason the AIIB matters is that it represents far more than a new foreign policy tool for Beijing to deploy on the way to cementing its status as regional hegemon.

The lender’s real significance lies in the degree to which it represents a shift away from the multilateral institutions that have dominated the post-war world economic order. In short, it’s a response not only to the IMF’s failure to provide the world’s most important emerging economies with representation that’s commensurate with their economic clout, but also to the perceived shortcomings of the IMF and ADB. The AIIB isn’t alone in this regard. Indeed, the BRICS bank can be viewed through a similar lens.Â

It’s against this backdrop that we bring you the following insight from Nomura’s Richard Koo, who suggests that the Greek experience with the IMF shows how the institution sometimes fails to deliver and by extension, how important it is for the countries in need to have more than one option when it comes to securing crucial aid.