I completely understand the confusion regarding bank reserves. I really do. It’s easy to believe they are money because that’s what you’ve been taught from Day 1. Not only that, the same message is carelessly reinforced in the media every single time QE or any LSAP is referenced. Bank reserves are the aftermath of money printing, therefore = money.

That was never really the case, however.

George M. Coffin, perhaps the pre-eminent banking expert of the Gilded Age, wrote several books on the topic of banking. He was at the time employed by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the chief regulator for all national banks. By the mid-1890’s, he had risen to Division Chief of OCC’s Division of Reports. It made him the head supervisor of all national bank examiners.

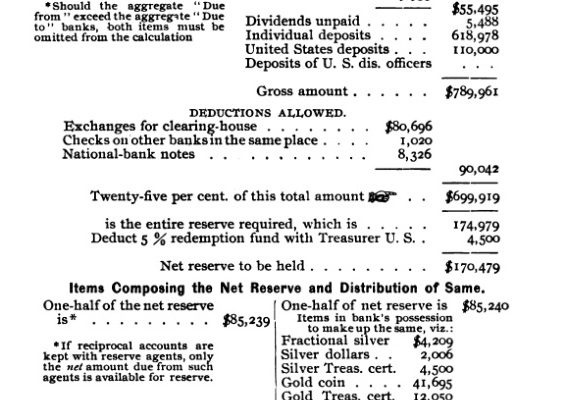

What he left us in his books is a precise glimpse of banking at that time. What you see above is the traditional relationship between actual money and reserves. The bank shown above, a reserve city bank, was required to hold half its obligation in the form of actual cash in a vault. The other half, conceptual reserves if you will, were primarily made up of correspondent balances (“balances with approved reserve agentsâ€) with other reserve city or central reserve city banks.

These were functional deposits that arose out of necessity of an increasingly nationalized economy – a national payment system. And it was this system which often spread contagion from one section of the country entertaining deposit flight to others.

In Coffin’s example shown above, if the bank in question had been subject to a run, say, on its holdings of gold coin (as had happened to a great many national banks in the Panic of 1893), it wouldn’t take much withdrawal for the bank to fall below statutory requirements. To anyone paying attention, that would propose a shaky bank in fact rather than just in rumor and therefore exacerbate any flight.

How would that bank be able to remain in business?

It would either call in loans, liquidating them for whatever cash it could obtain often at firesale prices, or it could convert its correspondent balances by requesting cash payment (specie). That, of course, would reduce the reserves of the correspondent bank, creating liquidity problems for it, and so on and so on.

The role of the central bank, in this case the Federal Reserve, was to be able to create reserve balances outside of specie. A central city bank, the precursor idea for primary dealers, could deposit collateral with its local Fed branch and in turn be sufficiently supplied with “bank reserves†of the kind we are familiar with today; a ledger credit on both the books of the Fed branch as well as satisfying the statutory reserves of the central reserve city bank.