From Morgan Stanley’s Cyril Moulle-Berteaux and Sergei Parmenov, who pick up where our simple chart showing China’s “debt nightmare” left off.

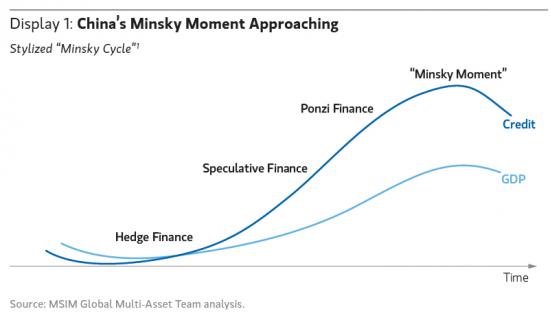

We have described in detail over the past two years how we believe China’s twin excesses (excessive investment funded by excessive debt) will inevitably unwind, causing a substantial slowdown in China’s economy, significantly below market expectations. In recent weeks, a trip to the region and further research into China’s shadow banking system have convinced us that China is approaching its “Minsky Moment,â€Â (Display 1) which increases the chances of a disorderly unwind of China’s excesses. The efficiency with which credit generates economic activity is already deteriorating, as more investments are made in non-productive projects and more debt is being used to repay old debts.

Based on our analysis, our baseline case is that China may slow from the current level of 7.7% Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth to 5.0% over the next two years. A disorderly unwind could take Chinese growth down to 4% in a shorter time frame with potentially disastrous consequences for levered Chinese assets (banks, property) and the entire commodity supply chain (commodity stocks, equipment stocks, commodity-sensitive countries and their currencies).

The consensus is more optimistic and expects China’s economy to grow by 7.4% in 2014 and 7.2% in 2015. Most market participants have concluded that the Chinese economy, despite its excesses, will slow only moderately as the government successfully manages to “soft-land†the credit and investment boom and that, as a result, the impact on global GDP growth could be moderate and is not likely to derail the global developed-market-led expansion. However, one of the more controversial conclusions of our analysis is thatglobal economic growth could be impacted severely enough to cause a global earnings recession.

Â

Hyman Minsky was a neo-Keynesian economist who developed a theory called the Financial Instability Hypothesis, similar to the Austrian school of thought, about the impact of credit cycles on the economy. In his 1993 paper entitled “The Financial Instability Hypothesis,†Minsky identified three financing regimes that economies can operate under: the first, which he called hedge finance, is a regime in which borrowers have sufficient cash flows to meet “their contractual obligations,†i.e. interest payments and principal repayment, usually by having a large equity component in their capital structure; the second, speculative finance, is a regime under which borrowers have cash flows that are sufficient to pay interest but not to repay principal, i.e. they must roll over their debts; the third, Ponzi finance, is a regime in which borrowers have insufficient cash flows to pay either principal or interest and therefore must either borrow or sell assets to make interest payments.

Minsky stated that “it can be shown that if hedge financing dominates, then the economy may well be an equilibrium-seeking and containing system. In contrast, the greater the weight of speculative and Ponzi finance, the greater the likelihood that the economy is a deviation amplifying system.†His paper draws the following two conclusions: 1) that “the economy has financing regimes under which it is stable, and financing regimes in which it is unstable†and 2) “that over periods of prolonged prosperity, the economy transits from financial relations that make for a stable system to financial relations that make for an unstable system.†In essence, the longer an economic expansion goes on, the greater the share of speculative and Ponzi finance, and the more unstable the economy becomes.