‘Not a Nice Guy’

We would normally be inclined to like Hungary’s Viktor Orban, not least because he is widely despised by the EU nomenklatura in Brussels. He also happens to be a staunch anti-communist, which results in Europe’s political left instinctively disliking him. Left-liberals are usually in the forefront of the incessant outcry over Hungary’s alleged infringements of human rights and European values. One must therefore be careful when assessing the almost continual stream of vitriol that is directed against Orban in the media. However, as you will see further below, he is not entirely undeserving of it.

In recent interviews in the German-speaking press, Orban repeatedly pointed out that he is ‘not a nice guy’, that Hungary at present in fact does ‘not need a nice guy’, and that he ‘wasn’t elected to engage in mainstream politics’. He also stressed his patriotism and defended his support of Christian values, both positions that are considered politically incorrect in Europe.

Due to enjoying a two thirds majority in parliament, Orban’s government was able to alter Hungary’s constitution. No-one seriously doubted that it was in need of change. The old constitution was essentially a slightly altered version of the Stalinist 1949 constitution, provisionally adapted to a democratic environment. It had always been planned to replace it with a new constitution, but that never happened until Orban entered the scene.

Hungary’s new constitution even refers to God, in a phrase adopted verbatim from its national anthem. Mainly it entreats God to bless Hungary and help it to flourish.

In spite of its numerous politically incorrect passages, German constitutional scholar Rupert Scholz judges the new Hungarian constitution to be one that ‘by objective criteria is a modern, even exemplary, constitution’. However, as you will see below, this appears to be a somewhat naïve assessment.

Hungary’s Economy Recovers

Orban’s governing coalition (Orban runs the Fidesz Party, which is in a coalition with the Christian Conservative Party) has chased the socialists from power in Hungary, inflicting almost irreparable damage on them. The socialists under Ferenc Gyurcsány ruled Hungary for two consecutive legislative periods, from 2002 to 2010. The country found itself economically in ruins and nearly insolvent when their reign ended. Public debt soared from 53% of GDP to 82%. This unhappy state of affairs helped sweep Orban to power in 2010.

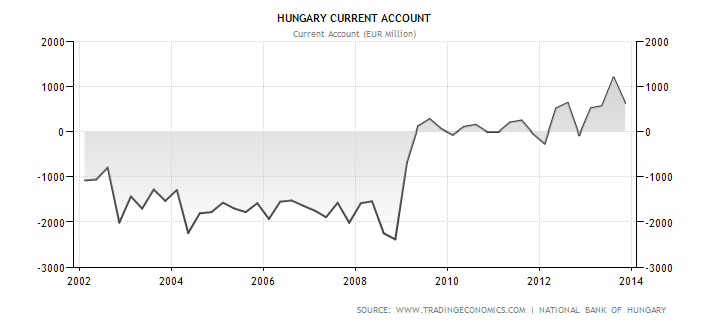

Hungary has left the economic crisis behind in the meantime, even though Orban’s populist economic policies leave a lot to be desired. Orban preferred to eschew IMF support, as he didn’t agree with the IMF’s prescriptions. Today, Hungary runs a current account surplus, which has lowered its dependence on foreign funding. As can be seen below, a number of economic data have actually improved significantly:

Hungary’s current account has moved from a perennial deficit to a surplus – click to enlarge.

Hungary’s rising foreign exchange reserves mirror this development – click to enlarge.

CPI has begun to decline sharply, however, this is in large part attributable to the government introducing price controls on energy prices – click to enlarge.

After touching the post crisis high of just below 12% several times between 2010 and 2012, the unemployment rate has finally begun to decline noticeably – click to enlarge.

The 2014 Election

In the election last weekend, Fidesz received 44.5% of the vote, which is very likely enough for the coalition to retain its two thirds majority in parliament. The alliance of the left led by the socialists only received about 26% of the vote, an outright debacle for the formerly strongest party in Hungary.