When it comes to the topic of the marginal utility of debt, or how much GDP does a dollar of debt buy (an example of which can be seen here), most people are aware that the developed world is facing ruin: with debt across the west already at record, nosebleed levels, and with GDP growth slowing down (due to capital misallocation, thank you Fed, demographic and productivity reasons), it is only a matter of time before it doesn’t matter how many trillions in debt a given treasury will issue (and a given central bank will monetize) – the credit impulse will simply not translate into incremental economic growth.

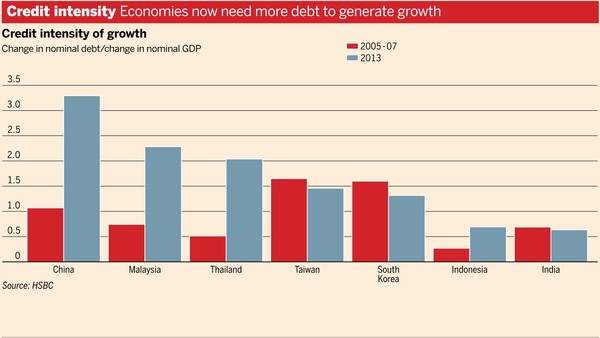

But did those same people also know that Asia is almost as bad if not worse as the west when it comes to the marginal utility of debt, or as the FT calls, it credit intensity.

Here, in three simple charts, is a visual summary of Asia’s debt trap:

Asian economies have experienced a surge in credit intensity – a measure of the borrowing required to generate a unit of growth

Rising consumer and corporate debt – some infrastructure and construction-related – has helped growth at a time of weak exports

The low cost of credit has helped growth, delaying structural reforms in countries including China, India and Indonesia

Some further thoughts from the FT:

While much has been written about China’s debt addiction, the experience is far from unique within Asia. Credit levels have risen sharply since 2008 in Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia, while already high levels of household debt in South Korea and Taiwan have tracked even higher.

During times of accelerating growth, that might not be a cause for concern. But now much of Asia is faltering. Credit intensity – the amount of borrowing needed to generate a unit of output – has surged, while productivity growth has tumbled. The debt train appears to be fast running out of track just as the world prepares for higher interest rates.

“There’s no problem in having the debt to GDP growth go up. It doesn’t have to collapse necessarily as long as you can turn around productivity growth,†says Fred Neumann, Asian economist at HSBC. “The big problem Asia faces is to implement structural reforms that are politically unpalatable before a crisis actually occurs.â€