A friend of mind asked me to comment on the Nanex article Perfect Pilfering, a detailed exposé on how the market is rigged from a data-centric approach.

We received trade execution reports from an active trader who wanted to know why his large orders almost never completely filled, even when the amount of stock advertised exceeded the number of shares wanted. For example, if 25,000 shares were at the best offer, and he sent in a limit order at the best offer price for 20,000 shares, the trade would, more likely than not, come back partially filled. In some cases, more than half of the amount of stock advertised (quoted) would disappear immediately before his order arrived at the exchange. This was the case, even in deeply liquid stocks such as Ford Motor Co (symbol F, market cap: $70 Billion, NYSE DMM is Barclays). The trader sent us his trade execution reports, and we matched up his trades with our detailed consolidated quote and trade data to discover that the mechanism described in Michael Lewis’s “Flash Boys” was alive and well on Wall Street.

The Setting

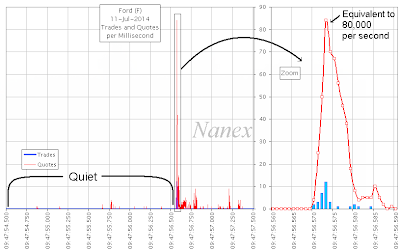

Let’s take a look at what we found from analyzing 5 large trades executed at different times over a 4 minute period in Ford Motor Co. Before each of these trades, the activity in the stock was whisper quiet. Here’s a chart showing millisecond by millisecond trade and quote counts in Ford leading up to one of these 5 trades:

You can clearly tell when the trade hits: activity explodes to over 80 quotes in 1 millisecond (this is equivalent to 80K messages/second as far as network/system latency goes). But the point here is that nothing was going on in this stock in the immediate period before this trade hits the market.

Continue here >