Speaking to accountants last week, several asked me if the Federal Reserve’s upcoming tightening wouldn’t increase the deficit. It won’t, surprisingly. It certainly seems that interest on the debt is an expense, and like any other expense, if it goes up, the deficit worsens. Sounds reasonable, but it’s not true.

The key to the puzzle is the conditions under which the Fed will tighten. They will only raise interest rates when the economy is strengthening, as an effort to fight inflation. When the economy is strengthening, though, the deficit tends to fall. A stronger economy generates more tax revenue, as total wages paid increases and corporate profits increase. So the time when the Fed will raise rates is when the deficit is getting better. Which effect will predominate? Theoretically, it could go either way. Historically, there’s no reason to believe that higher interest rates will worsen the deficit.

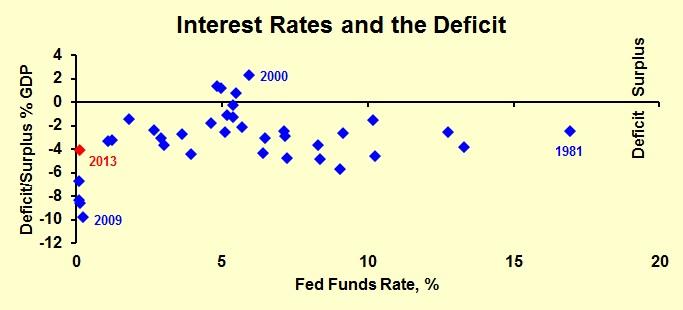

The chart below shows the deficit or surplus as a percent of GDP, plotted against the Federal Funds rate, the key short-term interest rate that the Fed controls. Note that points near the top of the chart represent years of surplus; points near the bottom represent large deficits. The data are plotted from 1977 forward.

There’s actually a bit of an inverse correlation: higher interest rates imply lower deficits. When the deficit was at its worst, the Fed kept interest rates extremely low. It’s certainly true that when the Fed pushes interest rates up, the deficit will be higher than it would have been without Fed tightening. However, it will simply be going down at a slower pace than otherwise. And the Fed’s mandate to keep inflation in check is critical to a healthy economy.

You’ve got lots of things to worry about. The Federal Reserve causing the deficit to go up should not be one of them.