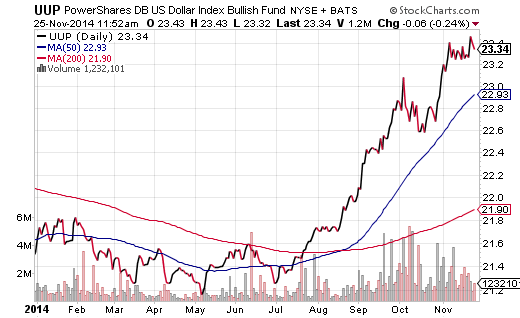

According to updated GDP reports, the U.S. economy grew at its fastest back-to-back quarterly rate since 2003. Yet few would attribute the U.S. dollar’s surge against competing currencies to the upbeat news. Rather, the dollar’s ascent is mostly a function of declining economies in Europe and Asia. Even the most ardent optimists realize that the dollar’s strength began in July in a summertime flight to perceived safety.

Still, many can still argue that the greenback’s dominance is not entirely related to protection. Indeed, it may be part of the global carry trade – the world’s investors borrowing or shorting the euro and the yen to invest in the dollar and/or more promising assets. It follows that the dollar’s victory may be partially attributable to the protection of capital and partially attributable to other factors.

In contrast, if the U.S. economy is so strong – if there is a manufacturing or service sector renaissance occurring in America – why have the safest of the safe harbor investments, long-maturity U.S. treasuries, defied economists throughout 2014? One should be able to recall that virtually every major economist from every significant financial institution had predicted rising interest rates in the year. How is it that so many folks could be so wrong about the direction of bond yields, the flattening of the yield curve and the monstrous gains in long bonds? My year-long contrarian recommendation, Vanguard Extended Duration (EDV), is up an astonishing 34% year-to-date.

Even gold, which has been in a near death spiral since mid-July, has been a little less ugly in November. With deflationary pressures bearing down on the Eurozone, China and Japan, how might we account for the recent intrigue in the precious commodity?

It is true that the Russian central bank has been loading up on gold, physical demand in China has been on the upswing, India has been considering import curbs and Switzerland is in the process of considering a key referendum. Those may all be impacting the yellow metal favorably. At the same time, gold is an asset more typically associated with inflation, not deflation. And that may mean fears of currency debasement based on the unconventional monetary policies occurring in Europe and Japan – the kind of policies that led to gold’s 2009-2011 record push towards $2000 per ounce – are also at play.