There is a real and frightening conundrum that has arisen from the Great Recession. It is the IOR Conundrum. What are we to make of payment of interest on excess reserves (IOR), held for the banks by the Fed? In a nutshell, the Fed says a floor must be created under the Fed Funds rate, which is a form of interbank stimulus, and IOR does that, while the Market Monetarists say that the Fed made the recession much worse by paying the IOR. So, which is it?

Many don’t realize that the Fed says it gave interest on banks’ reserves in order to put a floor under the Fed Funds Rate. The Fed is worried that banks would loan money between each other at lower rates than the Funds rate, perhaps leading to negative rates. Of course, the Funds rate has hovered under 1 percent, so you wonder what bank would actually do that. But here is what the Fed says:

Essentially, paying interest on reserves allows the Fed to place a floor on the federal funds rate, since depository institutions have little incentive to lend in the overnight interbank federal funds market at rates below the interest rate on excess reserves.

We all want to be free from the horrible Scandinavian problem of negative rates. We all know by now, I hope, that this has become a serious reality show over there in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, with the biggest Norwegian bank recently calling for a ban on all cash. We certainly don’t want to try their little experiment in cashlessness.

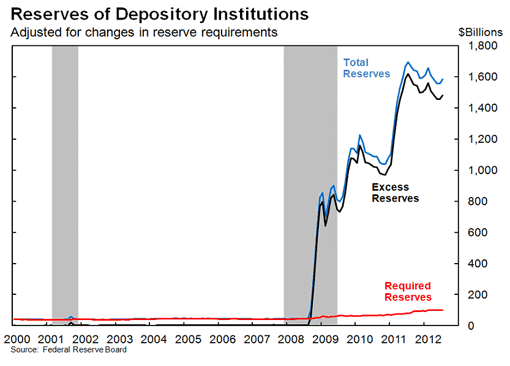

But the conundrum continues with the Market Monetarists showing pretty clearly that the Great Recession got worse because banks not only did not lend below Fed Funds rate, but they simply didn’t lend at all except to big business. The MMers view interest on reserves as a monetary policy tightening.

The Fed disagrees:

A steep rise in excess reserves cannot be interpreted as evidence that the central bank’s actions have been ineffective at promoting the flow of credit to firms and households.