“We have a system that increasingly taxes work and subsidizes non-work.â€

– Milton Friedman

“You must be the change you wish to see in the world.â€

– Mahatma Gandhi

“Real change requires real change.â€

– Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich

Today we come to part 3 of my tax reform series. So far, we’ve introduced the challenge and begun to describe the main proposed GOP solution. Today we’ll look at the new and widely misunderstood “border adjustment†idea and talk about both its good and bad points. What follows may make more sense if you have first read part 1 and part 2. Next week we’ll explore what I think would be a far superior option, though one that is based on the spirit of the current proposal. If House leadership thinks they can get the present proposal through (doubtful), then they should stop messing around and do something really controversial by changing the entire terms of engagement. As my friend Newt Gingrich has often told me, “John, real change requires real change.†Â

Warning: There is something in this series to offend almost everyone. Everything is fair game. If nothing else, I hope that no one can accuse me of simply talking the Republican book. I think this letter will pretty much eviscerate the key component of the proposed Republican tax plan. I hope the plan will be seriously changed. Many of you have direct contacts with your Senators and Representatives on both sides of the aisle. I urge you to send this letter to them and talk to them. This is one of the most serious national conversations we have ever had.

We can all argue about how big government should be, but whatever we decide upon, we must pay for, if not through taxation then through a massive debt-deflationary depression or serious inflation. (Next week we’ll talk about how to avoid these problematic outcomes. Yes, it can be done.) It’s not a question of cost or no cost, it’s a matter of who will pay and how much. The question is how to allocate the cost efficiently, equitably, and with the least possible economic distortion.

I have talked to many of the participants in the tax reform process, both in Congress and in think tanks. The one point of agreement is that the tax system must be massively reformed. That point, unfortunately, is where agreement ends. Tax reform ideas usually fail because the status quo gives everybody some kind of perceived benefit. In reality, the benefit may be worth less than people think, but it’s preferable to the uncertainty of a new system. This is basic game theory stuff, where the status quo is seen as what the economist types would describe as a “Nash equilibrium,†or a situation in where everybody has figured out how to make the system work for them, whether or not they are happy with it in toto. As long as nobody disturbs the equilibrium, things go on as they have done – until they don’t.The topic of equilibrium is one we’ve covered in past weeks, and we’ll be returning to it.

Last week I described the tax reform ideas that House Speaker Paul Ryan and his caucus include in their “Better Way†blueprint. As I said, there’s a lot to like in their plan. There are parts of it I love. I am most enthusiastic about the pro-business/entrepreneurial encouragement they offer. Truly, we cannot resolve our national economic dilemma without growing the entrepreneurial and business side of our equation. One of the few things that the Paul Krugmans of this world and I agree on is that we must figure out how to grow our way out of the problems we face.

However, we must remember that the “Better Way†is simply a set of proposals at this time. President Trump announced on Feb. 9th that his economic team is drawing up its own “phenomenal†business tax reform proposal. He said the White House would reveal it in the next few weeks. We have no idea whether it will resemble the House GOP plan. We do know the president hasn’t sounded enthusiastic about the border adjustment tax idea. We are also reading about major pushback on the BAT from many Senators and Congressmen.

I’m not enthusiastic about the BAT either, to say the least. I fear it would come with serious macroeconomic side effects, and not just for the US. Cutting to the chase, when I say serious macroeconomic side effects, I am talking about its potentially triggering a global recession, which would mean a major bear market and a total reset of valuations in every asset class. Not the end of the world, but certainly not without pain and cost. Let’s pick up the story right there.

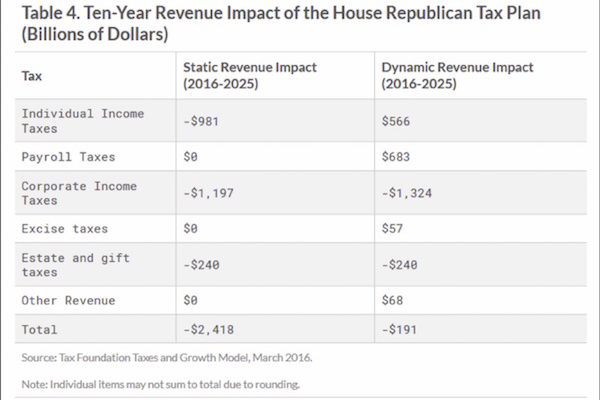

Before I describe how border adjustment works, let’s note why it is part of the Republican plan. The features I described last week, while attractive to many taxpayers, also cut deeply into the government’s tax revenue. Here is how the Tax Foundation calculates the plan’s impact, under both static conditions and a dynamic model that tries to assess economic changes.

Under static conditions, the plan would reduce tax revenue by some $2.4 trillion over ten years. A dynamic scoring reduces that amount to $191 billion. The reality is probably somewhere in between, but no one really knows. I tend to lean toward the dynamic scoring, but the plan is still not revenue-neutral in a world where the US is already running nearly $1 trillion deficits. I give Chairman Brady and the House Republicans (who are constitutionally responsible for initiating tax proposals) an A+ for trying to avoid increasing the deficit and the national debt with their tax cuts, and without offsetting the cuts with tax increases somewhere else. Seriously, two thumbs up! Longtime readers know I am a deficit hawk, and I appreciate the budget-balancing intentions of my fellow Texan who is chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. However, the tax cut proposals we discussed last week mean that Congress must find new revenue to make up for them. The border adjustment tax (BAT) is their idea to help fill that gap.

Here is how it works: Businesses that import goods from outside the US would not be able to deduct the cost of those goods from their corporate tax returns. But companies that export products to other countries would not count as income the revenue received from the exports.

The hopeful effect of this measure is to encourage exports and discourage imports, which is in keeping with President Trump’s objectives. It also helps offset the proposed lower corporate income tax rates that bring the US more in line with other developed countries. However, the proposal also assumes that running a trade deficit is something the United States should try to avoid. There are serious pluses and minuses to that view.

Most Americans may not realize how different our tax system is from those of every other country in the world. Almost every other nation has some variation of a value-added tax (VAT), a form of sales tax added at every level of production. Many also have corporate income tax, but the rates are lower than ours.

The House GOP plan (the red, dotted “Blueprint†line at the far right in the chart above) brings our corporate tax rates much closer to the average. Other countries make up the revenue gap with a VAT. The Better Way plan does it with border adjustment, which is sort of a halfway VAT.

The problem is that the US runs an enormous trade deficit because our whole economy depends on imports. We do not presently have the capacity to replace those imports with domestic goods. Can we build that capacity? Yes, but not overnight. In the meantime, this plan would cause prices for everything imported to rise sharply (think a 20% increase on much of what you buy at Walmart or Amazon), or the importers will go out of business, or both.

This is obviously not good for job creation if you are an importer. So what are the Republicans thinking? Why propose something that seems so daft? Well, in theory the BAT will bring in a lot of revenue, something like $1 trillion over 10 years if their assumptions are correct. This revenue is necessary to keep the Better Way plan’s other tax cuts from adding to the debt. And it will also theoretically increase jobs tied to exports. More on that below.

The Republicans also pitch the BAT as simple fairness. Other countries apply their VAT taxes to goods shipped by the US, so the US should do likewise. The problem here is that the US doesn’t have a VAT, so we’re adjusting for something that doesn’t exist. That makes this idea look less like an adjustment and more like an outright import tariff. In discussing this whole border adjustment concept with other economists, I find general agreement that my description of the BAT as a “half-assed VAT†is generally correct. That is perhaps not a politically correct way to state the matter in a letter that may be read by the faint of heart, but it does paint an accurate picture that will save you a lot of reading time, so I’ve just gone ahead and put it that way.

Here I need to stop and explain something. I believe that truly free trade helps everyone, but that’s not what recent so-called free trade deals have given us. Instead, they delivered something quite different from the kind of free trade that Adam Smith and David Ricardo envisioned. I explained this at length last July in “The Trouble with Trade.†Here’s an excerpt:

“Free trade†deals are no longer simple documents. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) weighs in at 5,544 pages. It’s a boatload of rules and regulations. I know there is talk that this deal was negotiated in secret, but that is far from the truth. You and I weren’t asked for input; but lots of people were, let me assure you. I can guarantee you that rice farmers in Texas and California were pressing their congressmen and others for access to the lucrative Japanese market, and Japanese rice farmers were trying to figure out how to limit the damage. For the record, Japan imports about 10% of its rice from the US, most of which they turn around and export as foreign aid or use for animal food. It is not that Japanese rice is that much better; indeed, the fact that US rice is so close in quality makes Japanese farmers nervous. And US rice is 1/3 to 1/2 the cost of Japanese rice.

Of course Japanese companies want access to US markets, where they can compete quite well, thank you, against US firms. And those US firms want to keep the protections and prices they have. This tit for tat has gone back and forth in hundreds of industries in the 12 countries involved in the TPP. I can guarantee you that wheat farmers or corn farmers or cattle or hog producers have a different view of the whole process than US rice farmers do. And their views are different again from those of equipment manufacturers or software developers, or pick any of 1,000 industries. Rice farmers in Japan have to negotiate terms of trade with other national industries, and do you think New Zealand avocado farms or sheep farmers or movie firms have any less interest in the process?

Every country is worried about US companies coming in and overwhelming their businesses, and the US is worried about “unfair†competition – that is, competitors in other countries producing products that are cheaper or better. Often, the higher cost of products here is attributable to the regulations that we impose on our own industries. So we want other countries to abide by our regulations (and they want us to abide by theirs).

The problem with global deals like TPP and its US-European counterpart, TTIP, is that while they may be good for the economies as a whole, citizens will find that “good†very unevenly distributed, which is why Trump calls such agreements “a job and independence threat.†After supporting the TPP for several years, Clinton now says she will not sign. Both candidates are responding to the very real problems generated by the uneven distribution of globalization’s benefits over the last 30 years [emphasis mine].