In September 2016, Wells Fargo fired 5,300 employees. These sorts of mass layoffs have become common in banking throughout the post-crisis era, especially those years of the “rising dollar.†This was different, however, as Wells was not cutting back in capacity but dealing with the aftermath of being far too aggressive. These employees were found to have opened secret and unauthorized customer accounts to charge fees in order to meet sales targets and therefore bonuses.

An internal investigation suggested as many as 1.5 million deposit accounts were created for this, as were 565,443 credit card applications. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued Wells a record $185 million in fines and ordered $5 million in restitution. In a memo to employees, the bank, as they all do, stood by its commitment to customers.

At Wells Fargo, when we make mistakes, we are open about it, we take responsibility, and we take action.

OK. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that once more Wells Fargo might have been doing wrong, this time having charged as many as 800,000 auto loan customers for auto insurance they didn’t need or want.

The expense of the unneeded insurance, which covered collision damage, pushed roughly 274,000 Wells Fargo customers into delinquency and resulted in almost 25,000 wrongful vehicle repossessions, according to the 60-page report, which was obtained by The New York Times.

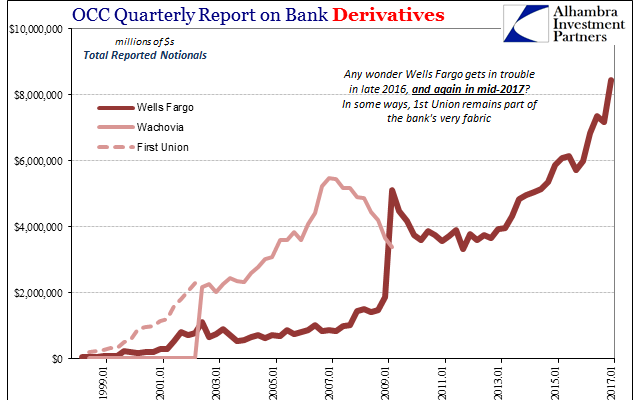

Wells Fargo used to be the sleepy behemoth providing mortgages far back from the front pages where firms like Citi (largest bailout in US history), Deutsche Bank, Bear Stearns, and Lehman were regular visitors. But that wasn’t really true, as the history of Wells Fargo in the post-crisis era is the absorbed history of firms like First Union and Wachovia.

No one should be surprised by the uncovered wrongdoing over the past year based on one single chart:

While other banks have been cutting back often severely in their derivative books, Wells Fargo has bucked the trend and charged ahead. As I wrote in May: