China is officially closed this week for its National Holiday Golden Week celebrations. These have been monetarily and financially eventful in the past because they represent challenges for RMB liquidity. This week appears to be no different, though this time it was the announcement of future policies that were no doubt written in the present tense of current monetary circumstances.

Starting in 2018, some Chinese banks will be eligible for a reduced RRR (reserve ratio requirement). The PBOC estimates that almost every bank of every size and business orientation will qualify for a 50 bps reduction, and that many might be able to achieve a 100 bps reduction for lending to small businesses or in the agricultural sector (if it sounds so very European in its targeting, it should).

There are several implications from this policy, all of which are more evidence of the major policy themes we have been following this year. Tightening in China’s money markets seems to have become excessive such that the PBOC felt it warranted in at least this measured response. That can only raise questions about the nature of tightening in the first place (who, exactly, is tightening what?).

The second relates to the idea of de-dollarization and a stable CNY, while a third has to do with “dollar†implications and what the Chinese appear to believe about possible monetary conditions in the year ahead.

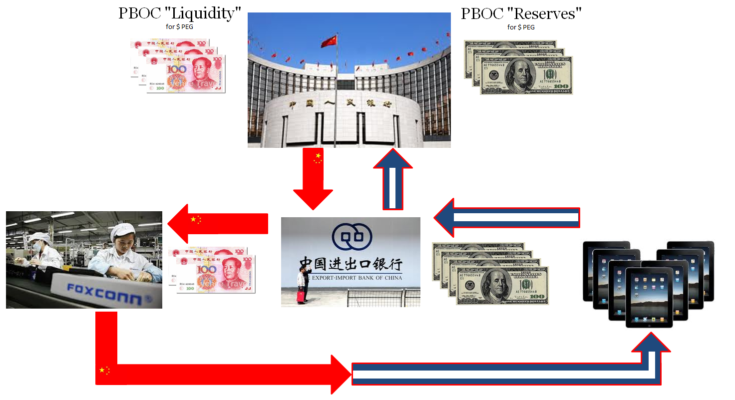

Those last two are both related in how the Chinese monetary system shifted through time since the major reforms of the early nineties. During the initial CNY peg period, the PBOC was at the center taking in dollars (and then more so “dollarsâ€) as the basis for its RMB expansion. On a peg, internal liquidity control (RMB) was simple and straightforward (doesn’t mean it was always easy).

(Click on image to enlarge)

The most basic structure is what most people picture as the Asian version of the petrodollar, or a mercantilist system that recycles dollars for goods. This isn’t correct, however, or is at least crucially incomplete. The amount of dollars (really “dollarsâ€) that were sent to China wasn’t really a function of the US trade deficit with that country. That mattered, but was amplified and augmented separately by investment flows (so-called hot money).